Draped

by Lizzy Vartanian Collier

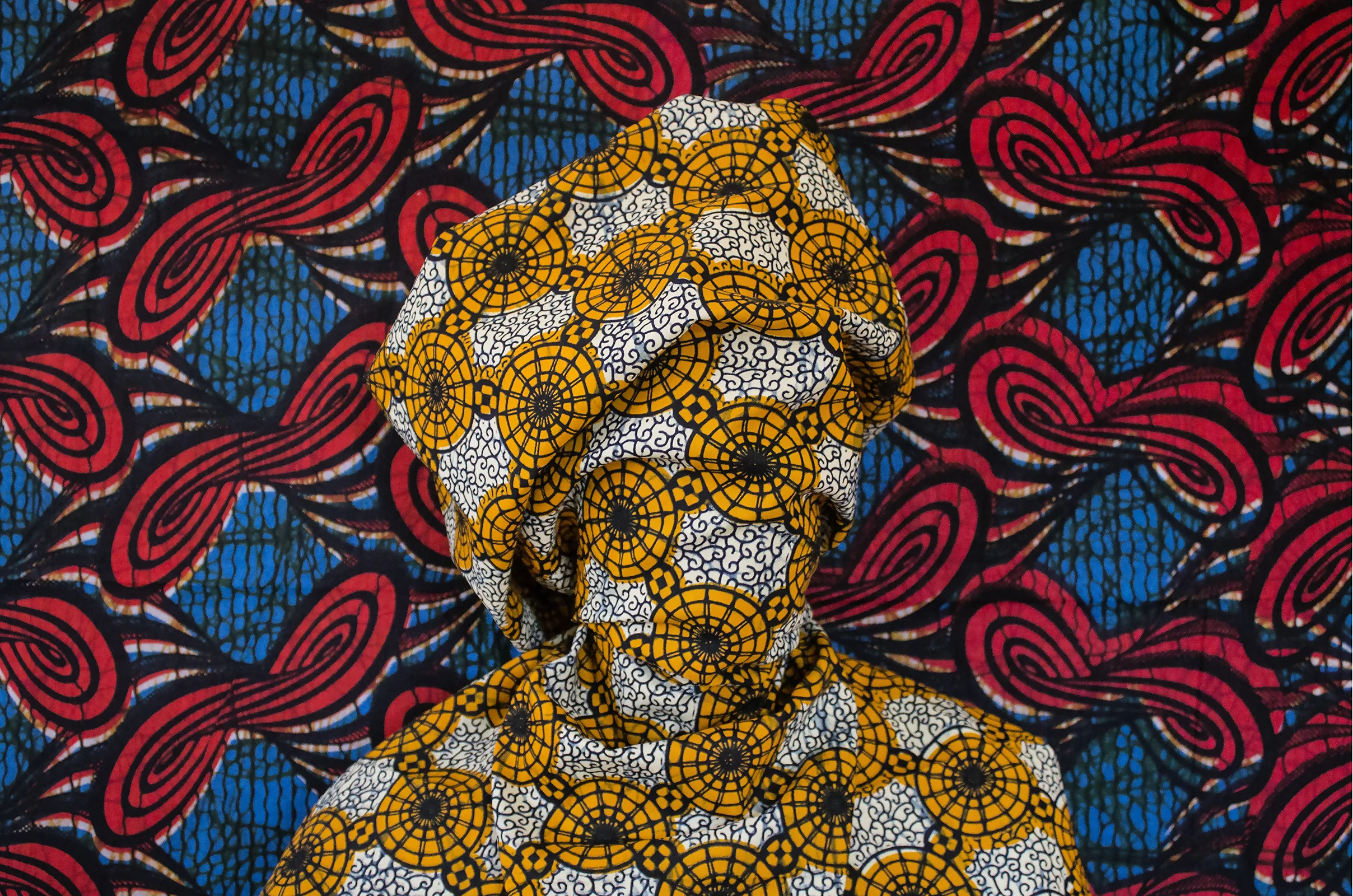

Alia Ali, Astral, 2017, BORDERLAND Series, 107 cm x 72 cm, photograph of pigment print on cotton rag

In Alia Ali’s series BORDERLAND, sitters pose for anonymous portraits, their faces and bodies completely covered in ornate textiles. To create the photographs, Ali—a Yemeni-Bosnian-American artist—travelled across the world to interact with textile artisans living in communities scarred by power and destruction. The resulting images depict what Ali calls ‘-cludes,’ a term which refers to whether the sitter is included or excluded in the portrait. As Ali writes for Still Harbor, “Who is on the other side of the fabric questions the very nature of belonging and interrogates the binary of home and exile. Is the subject the one who imposes the standards, the decision maker, the included? Or the excluded?”

Coming from two countries that no longer exist—Yugoslavia and South Yemen, growing up between Sana’a, Sarajevo, Istanbul and Indiana, and straddling Arab, European and American identities—Ali’s work challenges a singular understanding of identity. Ali uses fabric to question the borders that divide and unite us. “I have been collecting fabric for almost all of my life,” she says, “And I have been traveling for equally as long.” Having spent her childhood visiting markets across the world with her mother, she became exposed to different techniques of fabric making from a young age, realizing how difficult it was to pinpoint one particular source of production since many different influences impact the creation of a single piece of fabric—no matter how symbolic it may be of any one ‘culture’ or ‘nationality.’

Resplandor, 2017, BORDERLAND Series, 107 cm x 72 cm

Instead of focusing on borders that divide peoples and cultures, Ali’s attention is turned towards the places where cultures overlap. “I would argue that while man-made borders divide people, they do not necessarily divide culture; borders, in and of themselves, are cultural,” explains Ali. Borders are cultural as they separate one culture from another, creating dividing lines. Through BORDERLAND, Ali acknowledges that borders exist everywhere, whether they are manmade or naturally occurring. Borders can confine and block access, breaking communities and creating an ethos of fear and violence. “All these [borders] lend to an erasure of all that was,” adds Ali, “An erasure of what we see in these textiles. To me, communities that have a rich oral history express their stories and heritage through objects such as textiles.” Each piece of fabric tells a story of evolution, documenting the influences and histories of the cultures that led to its production. In fact, the word text comes from textiles, meaning ‘woven.’ However, as Ali explains: “Over time, those who wrote history were the ones who formed history; they are also the ones who form the perspective in which other societies are seen. So when we are discussing borders and societies with an oral tradition rather than a literary one, it is clear that these societies and cultures are misunderstood and seen through their suffering and their existence on these geographic physical frontiers, rather than through their beauty and knowledge developed over time.” Thus, the figures in BORDERLAND are ‘location-less.’ There are no identifying landmarks, no landscapes or objects in the background to enable the viewer to easily locate the subjects. The only markers of identity are the textiles that cover every inch of each sitter’s body.

The figures portrayed in the series present themselves in a number of captivating positions. From their posture, one gets a sense of the personalities of the people that might be hiding behind the fabric. “Posing really depends on the movement of the individual and the understanding of how the fabric falls,” explains Ali, “There is a mixture of me staging the scene and of the individuals beneath the fabrics really expressing themselves in it.” It is almost as though the figures are playing up to the camera, and perhaps, the fact that their faces are covered allow themselves to express their point of view in a way that may seem quite liberating in the way that their identity becomes ambiguous. “Some people feel very confined and limited as to what to do,” adds Ali, “Others, who might be shy in reality become completely expressive and performative when beneath the fabric. It’s really incredible.”

Mirrors, 2017, BORDERLAND Series, 165cm x 110cm

The artisans that perform for Ali’s lens have often been accosted by tourists who have little interest in the processes by whom these textiles were made. “Tourists tend to be interested in acquiring items for a bargain and on the way perhaps snap a photo without consent,” Ali says, subsequently describing the difference between a tourist and a traveler, “I try to be a traveler… talking, engaging, eating, walking, listening and learning from local people.” In fact, Ali does not reveal her camera until after discussing her project with the artisans, with many being more amenable to volunteer when learning that no skin will be shown.

Speaking about the reaction from the artisans being photographed, Ali explains the mutual understanding that the images aim to capture portraits of entire communities, not individuals. “Tribes survive as communal entities,” she says, “And there is something extremely beautiful about this that might be hard for Western Europeans or people of the United States to grasp, where people are extremely independent which is great, but also extremely lonely.” Ali sees tribal communities as ‘entire textiles woven together by years of stories and ceremonial histories.” She likens these societies to many different threads that are weaved together through listening and collaboration, two components that were vital to the fabrication of the series.

Ali intends for BORDERLAND to be an on-going series. “The words ‘border,’ ‘home,’ ‘homeland,’ ‘threat,’ ‘ban,’ ‘wall,’ ‘displacement’ are all too common in contemporary use,” she explains, “I don’t imagine them disappearing from our vernacular anytime soon.” We asked Ali whether media coverage about the UK embracing Brexit or the USA enacting the Muslim Ban or building a wall along the Mexican border is causing viewers to receive the work differently. “The work is certainly poignant in the UK and the U.S. at the moment,” she explains, “But the topics and themes covered in the series are certainly not new and are relevant to many parts of the world, especially in the places where I photographed.” In fact, it could be argued that Ali’s images are shedding light on communities where conflicts and struggles remain out of the news.

Emerald, 2017, BORDERLAND Series, 107 cm x 72 cm

While she continues to work on the series, she has just released a new body of work called [Laysa] Ana I AM [NOT], which also looks at what unites and divides us all at once, just like borders. In many ways, the images are very similar to those in BORDERLAND, with the figure’s identity disguised through a heavy cloak of fabric. But the fabric covering this figure unravels, revealing an underside that is woven differently to its colourful exterior.

This time the images are self-portraits; in every image it is Ali’s face that is hidden beneath the material. The work responds to the statement, I AM. “Through this series I investigate the theme in terms of what I am not,” explains Ali, “Essentially to label oneself is to willingly cast oneself in a static mold; and yet each day as we respond both to major events and to minute decisions, we recast who we are by discovering what we are not.”

Ali asks, who holds the power to create an identity? How can we break through the lens through which another views us? In the portraits, Ali uses woven newspaper to create a barrier between herself and the viewer. “I am both the photographer and the subject, the observed and the observer,” she explains. This new body of work questions the fabricated barriers in society that vilifies the other, borders that remain invisible.

Alia Ali encourages people to confront their prejudices by concealing her figures’ identities. By masking their faces with fabric or other means, we are already stopped from creating ideas about them from their exterior visual appearance. We know nothing about them, who they are, what they look like, where they come from. “Perhaps it is better for us to embrace the multiple layers of what creates our complex identities by living on the borders of all what we are, rather than continually struggling with abridged stereotypes imposed by others,” she says, “This leaves the question of what do we really know of anyone? Aren’t we all enveloped in stereotypes created by the other? The more we allow these labels to seep into our judgment, the more of a boundary we weave between each other, becoming both the victim and the culprit, all at once.”

Infinity, 2017, BORDERLAND Series, 107 cm x 72 cm

Lizzy Vartanian Collier is a London-based writer with a special interest in contemporary Middle Eastern Art. She has a BA in Art History and an MA in Contemporary Art and Art Theory of Asia and Africa from the School of Oriental and African Studies. She runs the Gallery Girl blog and has written for After Nyne, Arteviste, Canvas Magazine, Harper’s Bazaar Arabia, Ibraaz, Jdeed Magazine, ReOrient, and Suitcase Magazine. Lizzy is also curator of Arab Women Artists Now—AWAN 2018 (London).