The Sound Of

by Lizzy Vartanian Collier

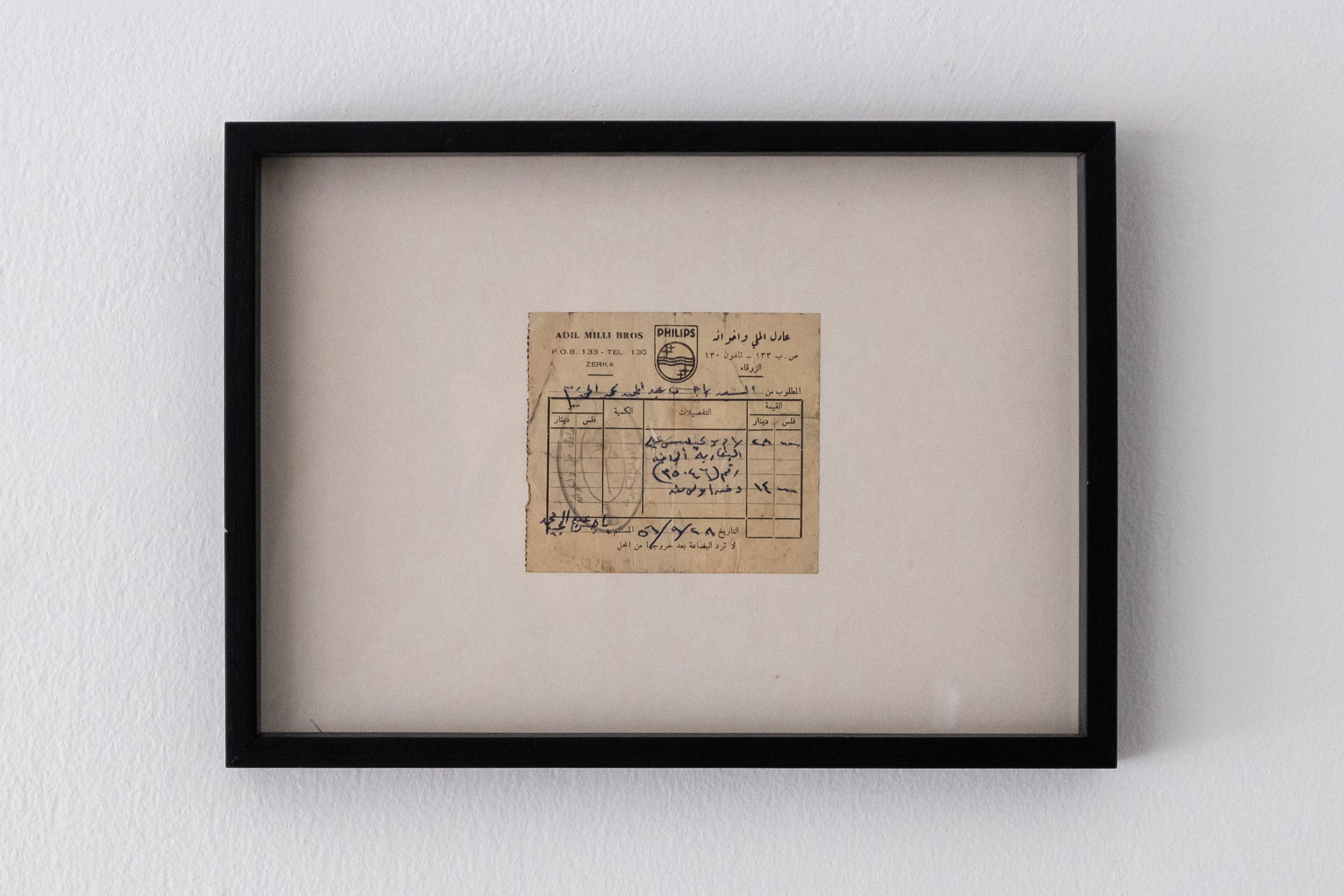

Invoice of first radio bought in Qalandia, Palestine. Courtesy of Darat al Funun.

Exhibition analyses how sound constructs social identity and space.

In 1956, the first radio was purchased in the Palestinian village of Qalandia. Bought by Mr. Bajis Abdul Majid, the owner of the village supermarket, the whole town would gather at the grocery store to listen to the broadcasts—and buy their khobz. The receipt for this radio is currently on display in Ephemeral Territories at The Lab at Amman’s Darat al Funun, an exhibition questioning how sound can be used as a tool to construct social identity and space. Working within the context of the Global South, the group show considers how narratives have been communicated to forge new nationalities and identities in the framework of a modernizing state; but also how sound can create spaces for alternative modes of being (especially for marginalizted groups); looking specifically at how technology and mystic practices can be used as forces of subversion.

Below the bill for the Qalandia radio, a set of headphones plays anecdotes and archival material including personal memories from when the technology was first introduced. The recordings explain how the radio was used as a political tool. “Without it, there would be no such thing as Arab nationalism,” explains a man from Hebron who was politically active in his youth, “It spread on the radio. [Gamal] Abdel Nasser’s speeches were aired all over the Arab countries. In many countries against him, the speeches were banned, so people would close their shutters and put the radio on very low to listen without being caught.” The same man recalls how, in 1956, the radio helped cultivate a transnational consciousness and shared sentiment amongst workers from the region leading to a boycott of Western ships by Algerian and Moroccan ports. In another testimony, a man recounts that during the 1967 Six-Day War, people gathered around the radio to listen to updates of the battle. “The interesting thing is that it turns out whatever was being communicated did not match with what was happening on the ground,” says Joud Halawani Al-Tamimi, the exhibition’s curator, whose father was in Egypt at the time. “Suddenly after having very high hopes because of what people heard on the radio, everyone was devastated by the effects of the battle.”

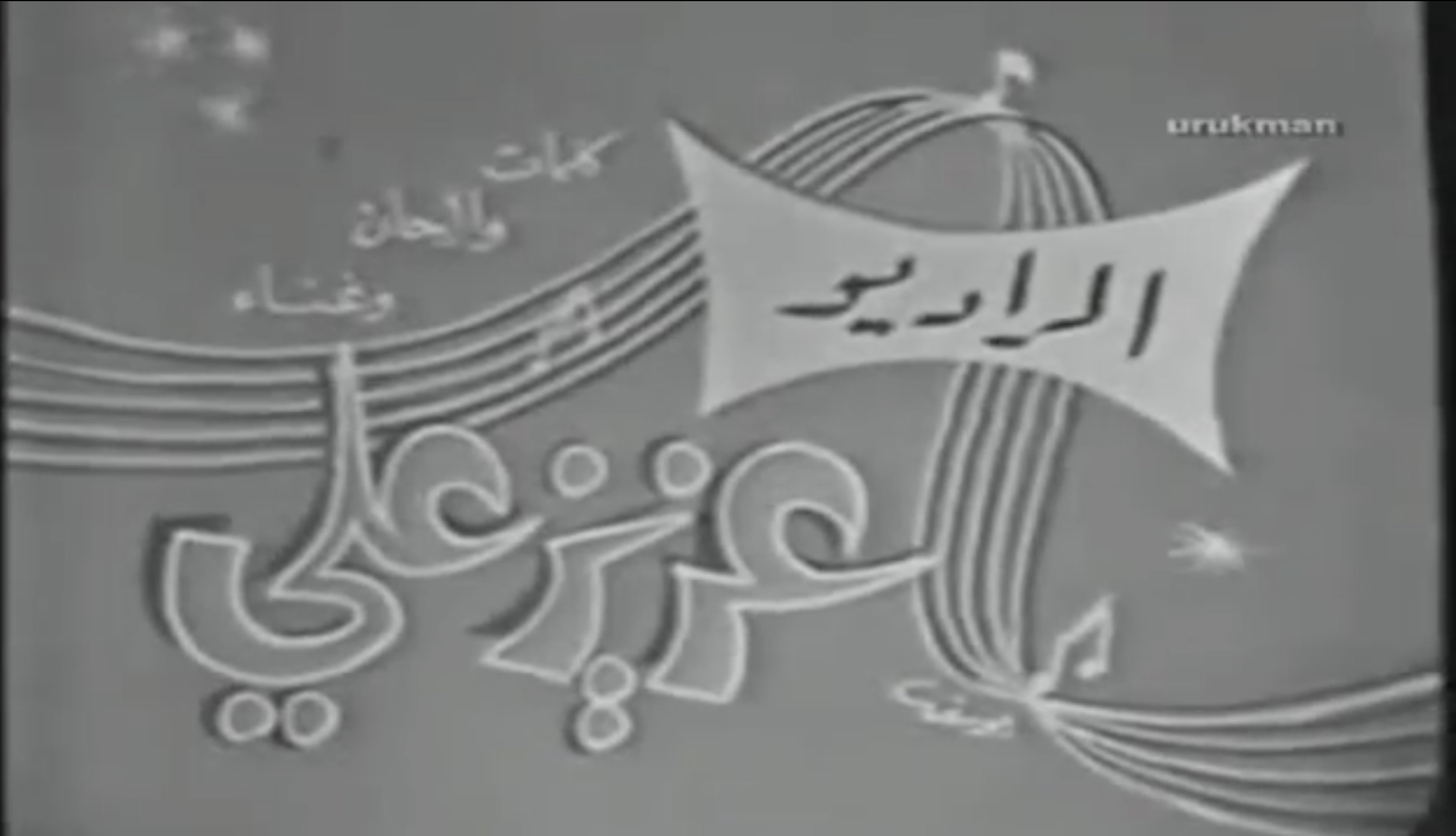

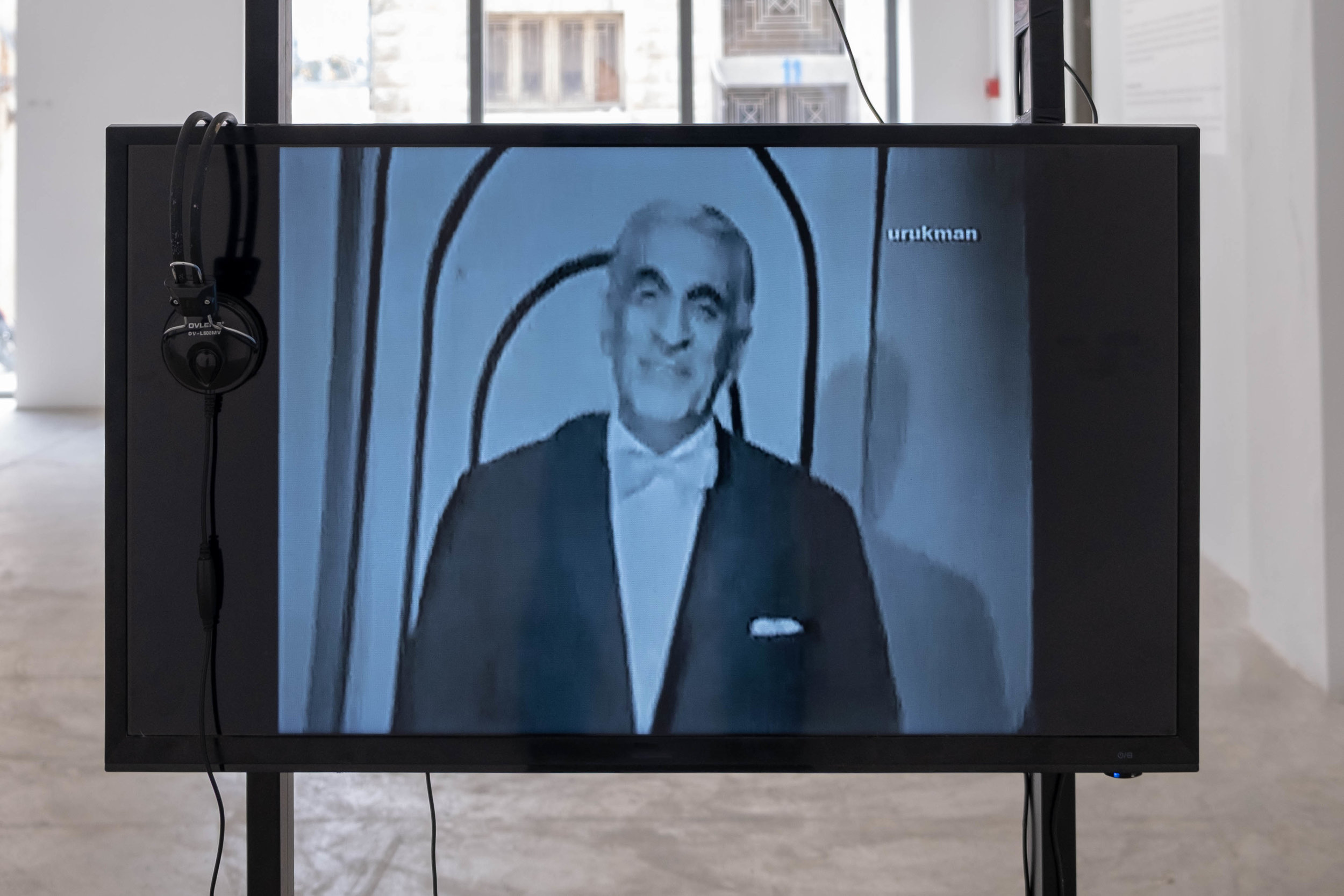

The political impact of the auditory is also demonstrated through Jean Bhownagary’s (b. India 1921) film Realm of Sound (1954), which looks at how the radio became a major feature of modernity in India. “Suddenly, people are all listening to the same thing at the same time and there’s a connection between people that were previously disconnected,” explains Tamimi. “In that sense, the radio became a tool to constitute what Benedict Anderson terms Imagined Communities.” Similarly, Aziz Ali (b. Iraq, 1911)—who was imprisoned more than once for his infamous monologues opposing the colonizer—illustrates just how unifying the technology can be. In Radio (1950s), he sings about it as an instrument for decolonization, democracy, and a symbol of free thinking.

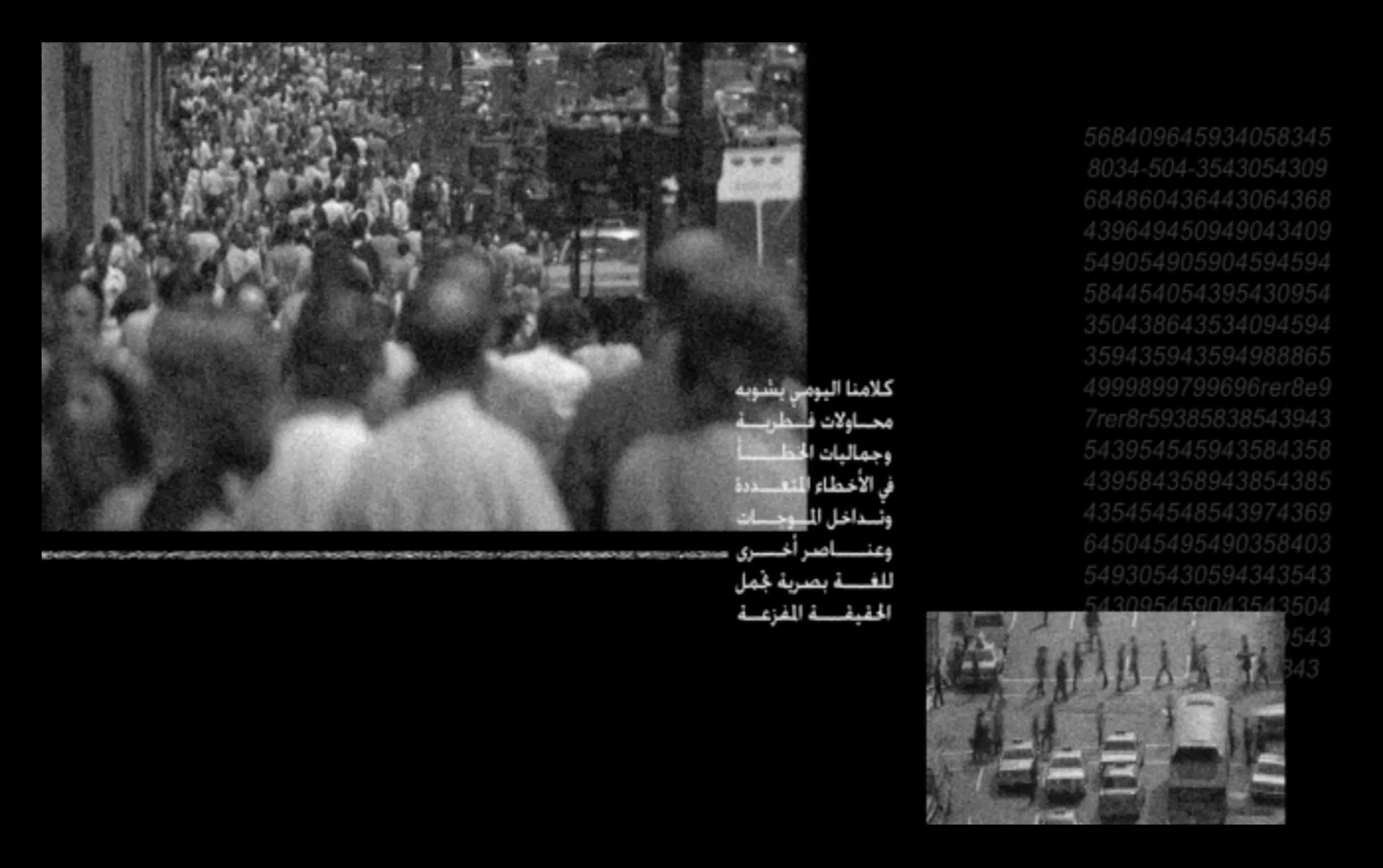

Installation shot, K. Hall (2019), by Basel Hasan, Diana Al Zubi, and Mostafa Onsy. Image courtesy of Darat al Funun.

That being said, the radio was more than just a means for spreading political ideas. There was a social-cultural aspect to it too. “More than one person explained how they would gather every Thursday at the end of the month to listen to Umm Kulthum’s concerts,” says Tamimi. “They would have sweets and a whole feast, as if they were really attending a concert.” Moreover, the radio was at one point the only mode of communication between people living in the East Bank and the West Bank of Palestine, sharing news of a cousin getting married or the birth of a child.

Beyond the radio, the multigenerational exhibition also considers how sound is introduced into alternative spaces to bring about different modes of beings and norms around experiences of shared listening. “How,” asks Tamimi, “do we think about alternative spaces critically?” Basel Hasan, Diana Al Zubi, and Mostafa Onsy’s K. Hall (2019) displays abandoned spaces, the locations where individuals and communities that are often marginalized and ‘othered’ find places to express themselves comfortably. The images are accompanied by headphones playing the music that would be heard within these peripheral spaces. “Noise is in and of itself, subversive,” adds Tamimi. “It’s outside structure and hierarchy; it’s a subversive force.”

Still from To the Black Sun (2014-2019) by Naresh Kumar. Courtesy of Darat al Funun.

Political and social subversion combine in the exhibition of Nassredine Bennacer’s (b. Algeria 1967) Erreur 404 (2016) and Bashar Suleiman, Yazan El Zubi, and Laith Demashqieh’s Thug Mojo (2019). Bennacer’s work consists of a map of colonial Algeria, which was made during colonial times, titled “La France.” In response to this, Bennacer has stamped “Erreur 404” over the top, pointing out that the map is incorrect. Next to it, a piece of fabric hangs from the ceiling adorned with shells, inspired by the garment worn by those who perform Zar—a community healing ritual involving musical performances in which women play a leading role. “The mystical practice is looked upon as subversive in a context where we are still feeling the effects of colonial legacies,” explains Tamimi. “Part of that rationalization came with modernity and laid the basis for the colonial project to begin. So the mystical, magical, and occult are looked upon as forces that redefine the lines between the rational or the irrational, the obtainable or the futile.” Below the fabric, the sound of Zar performances can be heard besides displays of drawings evoking healing and strength, complete with charcoal and chalk. The exhibition seeks to tap into postcolonial politics whereby the magical and mystical are proposed as tools of resistance in the face of the hegemonic discourse of the colonizer. Naresh Kumar’s (b. India 1988) film To the Black Sun (2014-2019) also illustrates how the performance of a spiritual ritual can protest a non-democratic or oppressive reality. The work’s inspiration comes from the Chhatt festival in the artist’s hometown of Patna, India. During the festival, Kumar would watch his father prostrate himself before the sun, paying obeisance to it. Within the film, however, Kumar layers his body with mud in reaction to a contemporary society, which he believes is rapidly blackening that sun.

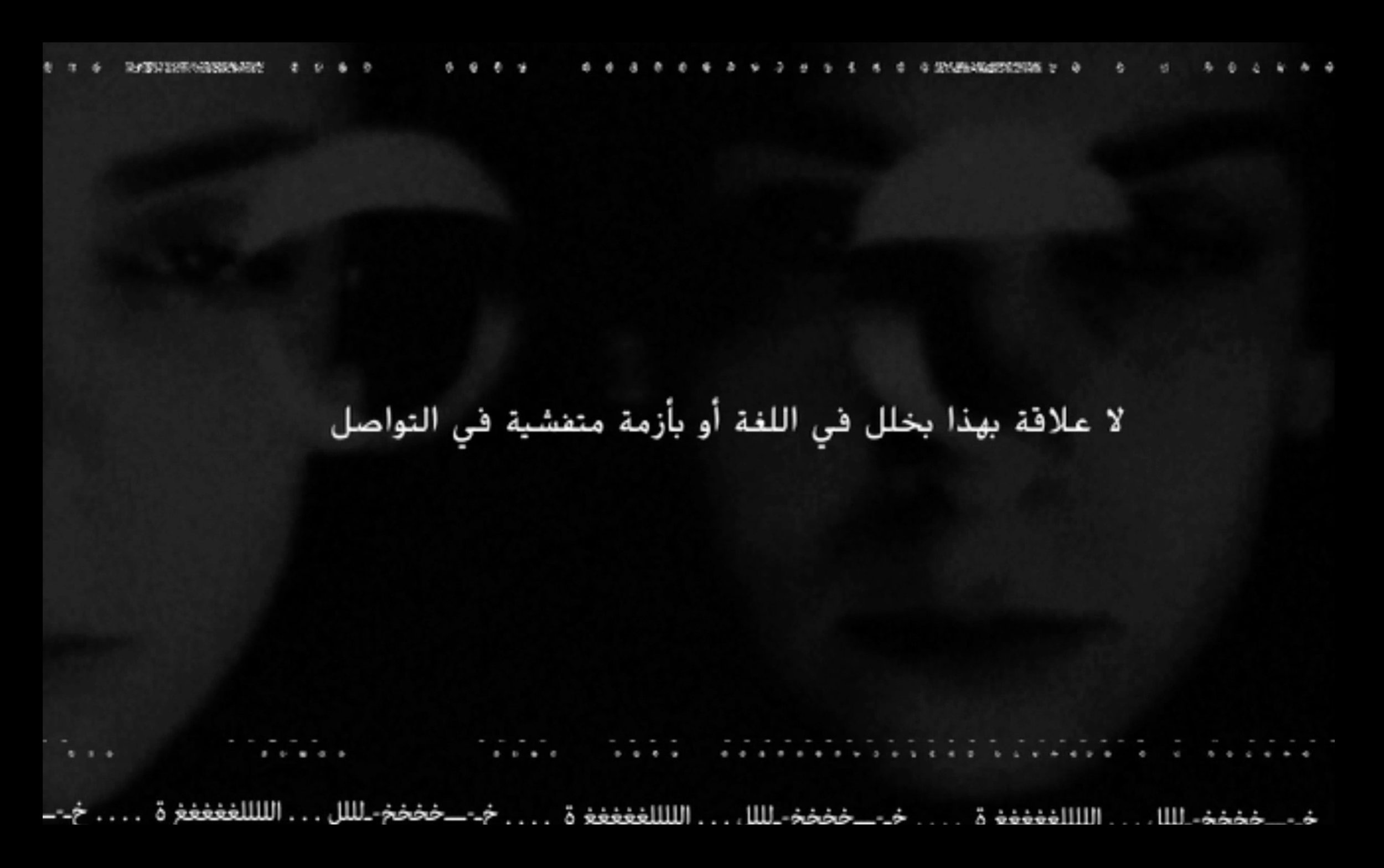

Still from Philosophical Suicide (2018) by Fai Ahmed and Magdu Magdy. Courtesy of Darat al Funun.

The reclamation of a future occupied by different voices is likewise evident in the work of Magdu Magdy (b. Kuwait, 1990). In Radical Empathy (2019, work in progress), an audio essay evokes magic incantations and feelings of disconnection. Looking at the feeling of being “othered,” the work asks how language(s) can be used to carve out spaces for the marginalized, and how it can also move beyond “capitalist realism.” Nawaf Radwan similarly meditates on language as a tool of resistance, albeit by deploying the written word as a form of inner sound. Ephemeral Territories concludes with Philosophical Suicide (2018), where Fai Ahmed (b. Saudi Arabia, 1990) and Magdy analyze the glitch as a subversive force. Composed of noise fragments, the video work deconstructs the absence of meaning and systems of failure while disrupting the miscommunications that govern everyday life.

Probing the social and the political possibility of the auditory, Ephemeral Territories explores the transformative and subversive potential of sound as a tool to construct alternative narratives and landscapes. The exhibition uses noise to disrupt the boundaries between the rational and the irrational, transcending failed ideologies and colonial legacies.

Ephemeral Territories runs until 9th April 2019 at The Lab, Darat al Funun; Amman, Jordan.

Lizzy Vartanian Collier is a London-based writer with a special interest in contemporary Middle Eastern Art. She has a BA in Art History and an MA in Contemporary Art and Art Theory of Asia and Africa from the School of Oriental and African Studies. She runs the Gallery Girl blog and has written for After Nyne, Arteviste, Canvas Magazine, Harper's Bazaar Arabia, Ibraaz, Jdeed Magazine,ReOrient, and Suitcase Magazine. Lizzy is also curator of Arab Women Artists Now - AWAN 2018 (London)