The Gathering

by Ajna Biya

This work appears in Khabar Keslan Issue 2. PASSAGE

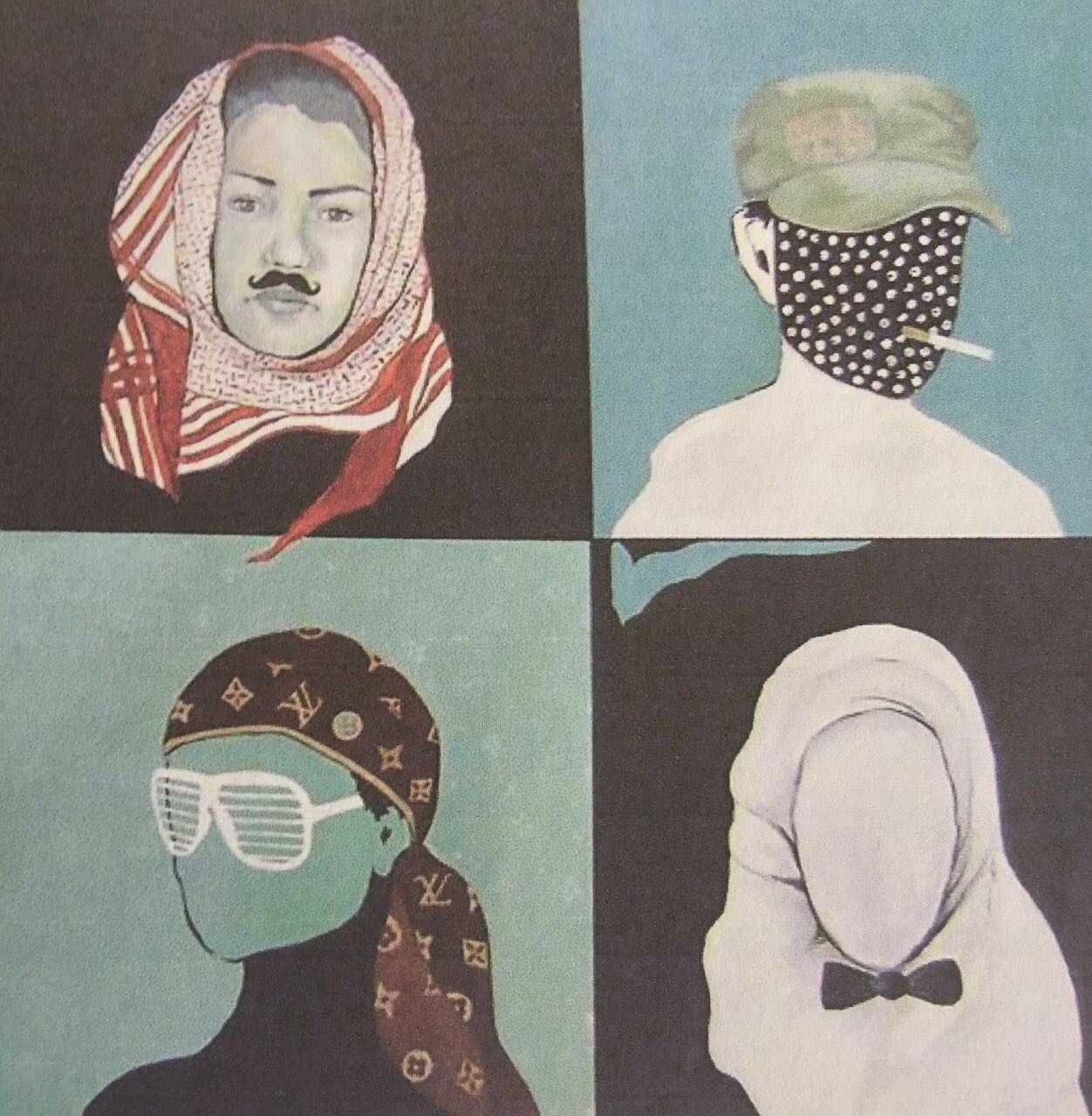

"The Saudi Muslim Communist Socialite Artist" by Layla Mossallem.

Five rules for surviving Saudi women's high society

When I first came to Jeddah in 1995, the women of my particular social circle had two main occupations in life: they shopped for luxury brand outfits, and they had lavish gatherings that required them to shop for luxury brand outfits.

Rule #1: You don’t want to be seen in the same outfit twice.

These women gathered daily; usually for lunch, sometimes for dinner, sometimes for both lunch and dinner. They gathered for other reasons too: to get out of their houses; to see the same people—even if they can’t stand them (and especially if they can’t stand them so they can gossip about them); to look for potential wives for their sons; to keep track of who got married, divorced, remarried, whose husband took a second wife, who gave birth, who was pregnant again, who changed her hair color, and who died. These women also gathered to check each other out. They were curious to see who gained or lost weight, who shopped where, and—since this was a time before Botox and fillers were invented—who looked older.

Women of this circle primarily gathered to eat. Food was offered in exaggerated abundance, as this was the mark of a hostess’ hospitality, and you would insult your guests if you did not produce enough food to feed the Russian Army. Also, you want everyone to get fat.

Unfortunately, my Russian communist mother did not prepare me for this lifestyle. Nor did she introduce me to any of the capitalist values that would have eased me into these new activities. I did not even know how to shop for clothes, and luxury brands meant nothing to me. I was raised to be frugal, to only buy what a human being needed to survive, like bread and galoshes. When I was growing up my closet consisted of clothes that I absolutely needed, mostly my school uniforms and underwear. I also had a few hand-me-downs. For those of you who don’t know, they are clothes that are handed down from kids who outgrew them; one parent gives a dress, another parent provides shoes. It doesn’t matter if they don’t go together and you end up looking like Pippi Longstockings—you wore them, and you were happy to have something new. Jeans were a luxury in the communist era, but believe it or not, I actually had a pair handed down to me, which I wore like the rebel that I was. I also had some T-shirts to go with the jeans. My family was progressive, you see.

So one sunny day in Jeddah, shortly after I settle here, my mother-in-law has a gathering. Of course, I have to be there, because now that I exist, everyone wants to see the new wife in town. What nobody bothers to tell me is that these gatherings are lavish affairs and that I have to make an effort to dress up, high heels, make-up, hair, and ATTITUDE.

Attitude is key to making an impression. You need to walk in theatrically, nose in the air, in a fancy abaya, without looking at anyone in particular, because having a bitchy attitude and acting like you’re better than everyone protects you from the jealous glances of toxic women, wards off evil eyes, demands respect and shows that you are from an upper-class family. You should smile coldly with your lips but not with your eyes, as is the protocol when meeting strangers; you should give three kisses in a certain sequence with a semi-bored look that says, “I don’t give a shit about you; just kissing you because I have to.” Then you should sit still with your back straight the rest of the evening like something out of a Victorian painting and stare into space, only speaking if spoken to, and limit your answers to three main words: Inshallah, Mashallah, and Hamdullah. You’re supposed to vogue your face like Madonna while they look you up and down and whisper to each other. When they are done, you could make small talk—but not smart talk—and never spend too long with any one person because conversations are for low-class women who talk too much.

Needless to say, I do not make my mother-in-law proud at this gathering.

I do not go shopping; I do not buy a new outfit.

I stumble into the room from the heat and humidity of Jeddah, all sweaty in my jeans, Harley Davidson T-shirt, and practical Converse shoes, no makeup, with my hair in a mommy ponytail, and my new baby in a kangaroo sling in front of me, his bare feet dangling from the sides. Instead of a classy bag, a huge Mothercare bag is slung over my shoulder that contains anything my baby might possibly need.

Disapproving looks cut through me like a Turkish sword.

Rule #2: Never bring your child anywhere without a nanny and never carry anything yourself unless it is a luxury brand bag.

Perhaps it is worth mentioning that at the time I was practicing something called “Attachment Parenting,” which requires you keep your baby physically close to your person at all times. He can hear your heartbeat as he did in the womb, feel secure and nurtured, develop healthy emotional ties, learn that the world is a loving, caring place, and thrive. I believed in this method and stuck to it firmly, carrying my baby around in a sling while I did household chores, went to the supermarket, or anywhere else. I only put him down when I was cooking or when I went to the bathroom, for obvious reasons.

Everybody thought I was crazy. Why would I spend so much time and effort on a meaningless little thing when I could be doing much more life-enriching and entertaining activities like shopping and going to gatherings? The maid will sit with the baby. What does the baby care anyway? He’s just a baby. He doesn’t know anything.

Rule #3: Never do anything yourself when you can have someone else do it for you.

I scan the room quickly, and it’s all a blur of make-up, hairdos, heavy perfume, and scrutinizing eyes, which disorients me. I move around the room randomly, not sure if I should shake hands or kiss or both, so I end up doing the awkward half-shake-half-hug-almost-kissing-people-on-the-lips, not knowing which way to turn for the next kiss, trying not to squash the baby and not get him too close to anyone so he doesn’t suffocate from their perfume. I smile a big, warm smile like I’m happy to be here with all you lovely ladies and your lovely smells. In my awkwardness, I blurt out stupid compliments to women I just meet about the color of their nail polish. I comment on color to a few more unimpressed women, probably because I am an artist, but mainly because I don’t know what I’m supposed to say or to whom.

I’m sitting there with my baby on my lap, and the dreaded whispering begins. People eye me suspiciously and whisper to each other, “That’s the daughter-in-law… She’s a foreigner… She doesn’t pray…”

Finally, somebody asks “How are you?”

“Inshallah good,” I reply.

“How is your husband?”

“Mashallah, he’s good.”

“How is your baby?”

“Hamdullah, he’s also good.”

“Do you love your baby?” one woman asks.

“Yes, Hamdullah,” I reply, dumbfounded.

Everyone smiles. Mashallah, everyone is good and Hamdullah, she loves her baby. Small talk is over. Not too painful. Hamdullah that was all they wanted to know about me and nothing else was of interest.

Rule #4: At least one of these three words, Inshallah, Mashallah, and Hamdullah, is a requirement in each sentence, especially in answering questions about husbands and children. You can use two together for extra credit.

Maids in pastel colored uniforms bring out tea, coffee, juices, and begin serving dates and other snacks while more maids bring out the shishas. Soon everyone is smoking and discussing various topics. First, they compare drivers: “You can’t believe how annoying my Indonesian driver was yesterday. I told him to go left, and he went right! We kept going round in circles, and by the time we reached the Boutique it was prayer time, and they closed already! I wanted to buy a new blouse, like the one I bought last month but a bigger size, for some reason that one got small on me…”

“Well, my Indian driver is more annoying than yours; he doesn’t understand a word I say! The other day I told him to buy Otrivine from the pharmacy, and he went and got an electrician to fix the TV… I almost got a heart attack all -of a sudden I see this man walking into the house asking where is the AC that needed fixing!

“Well, my Pakistani driver is the worst. He keeps forgetting to buy Pepsi. I explained to him a billion times my husband can’t eat if there’s no Pepsi. He doesn’t know how to take care of us; he just doesn’t get it that we can’t live without Pepsi…”

Another group of women is talking about the Cooking Show and comparing recipes, each one arguing that hers is the original one. Then they start talking about another TV show like it’s for real.

“Can you believe she showed her hair to her husband’s brother? She’s such a slut!”

“Well, her husband was beating her because he didn’t like her cooking.”

“Well, that doesn’t give her the right to go running off without a tarha! Besides, she should watch the Cooking Show and try harder; she’s giving us all a bad name, I bet you anything she’s going to have an affair with her brother in law. Either tomorrow or the next episode.”

I’m sitting there thinking this better be over soon before I kill myself and thankfully my baby starts to cry. I make an excuse to my mother-in-law about it being too smoky for the baby, hurriedly pick up my stuff and leave.

“Why is she leaving?” one woman asks. “Doesn’t she want to stay with us?”

“Of course she does,”my mother-in-law says politely to her guests, “but she has to go cook for her husband.”

Approving glances stab like a thousand Turkish swords as I realize that, to them, this would be the only acceptable excuse.

You really don’t want to know the details of what happened post-traumatically, but my husband had to buy his mother a really expensive luxury brand bag to apologize for my behavior. What pissed her off the most was not that I did not dress for the occasion, or that I brought my baby—but that I did not stay for the food, the whole purpose of the gathering.

Rule #5: Always stay for the food.

Ajna Biya is a Saudi writer and artist, who uses satire to portray her social experiences, and her adaptation to Saudi cultural norms. In her sarcastic comedic style, she describes personal incidents that her memories hold dear. Throughout her 25 years in Saudi, she has developed a healthy sense of humor which has guided and helped her grow into the Saudi environment, which she loves and calls home.