Home and Belonging: An Interview with Hava Toobian

“If I understand a queer diasporic person as someone who time and time again has to recreate a home, then place-making is a reoccurring aspect of [their] lives.”

Meet Hava Toobian: a Jewish Iranian Kurdish woman, artist, and parkour extraordinaire. In this interview, she delves into her latest show, Home and Belonging, representing her interest in queer diasporic theory and critique.

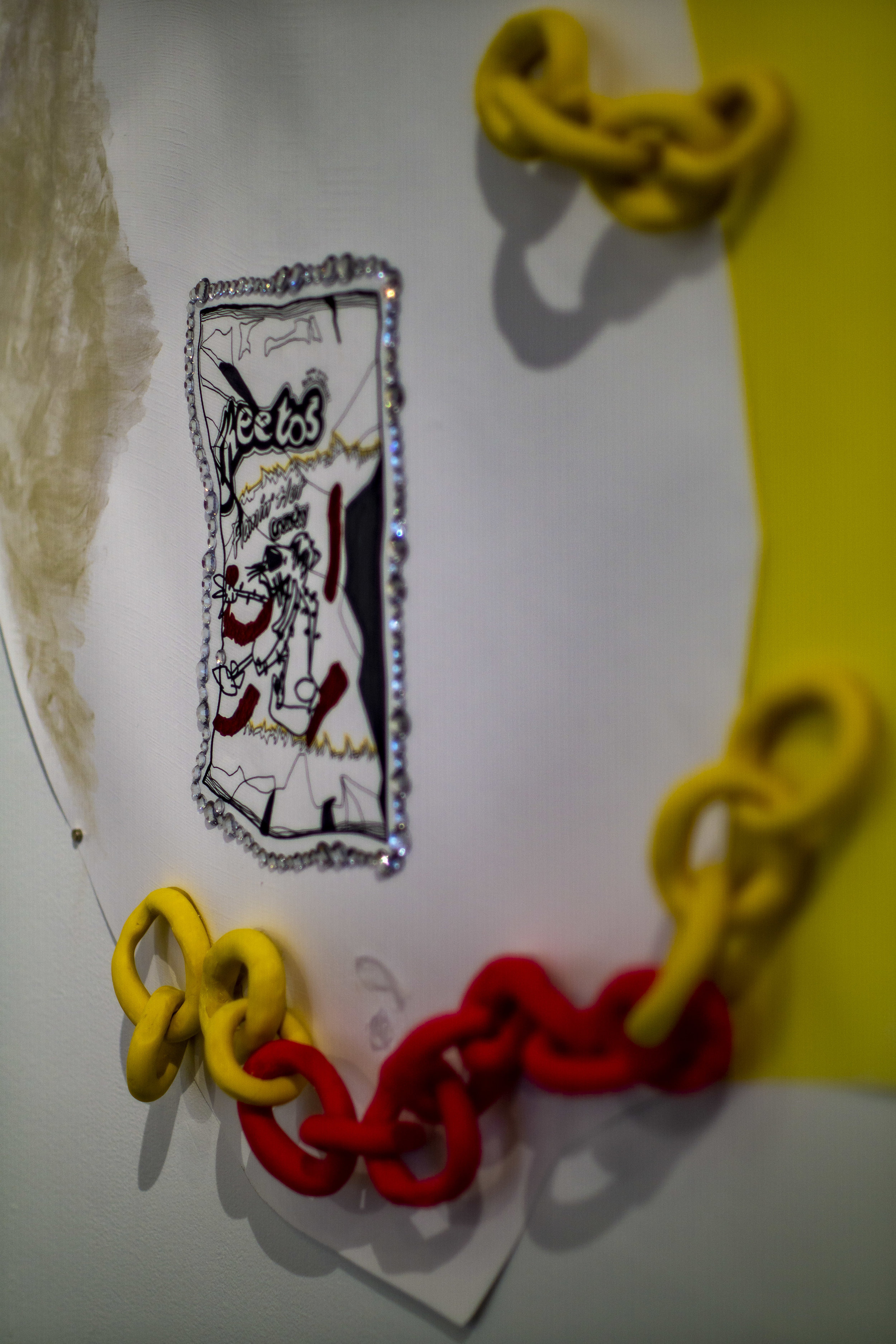

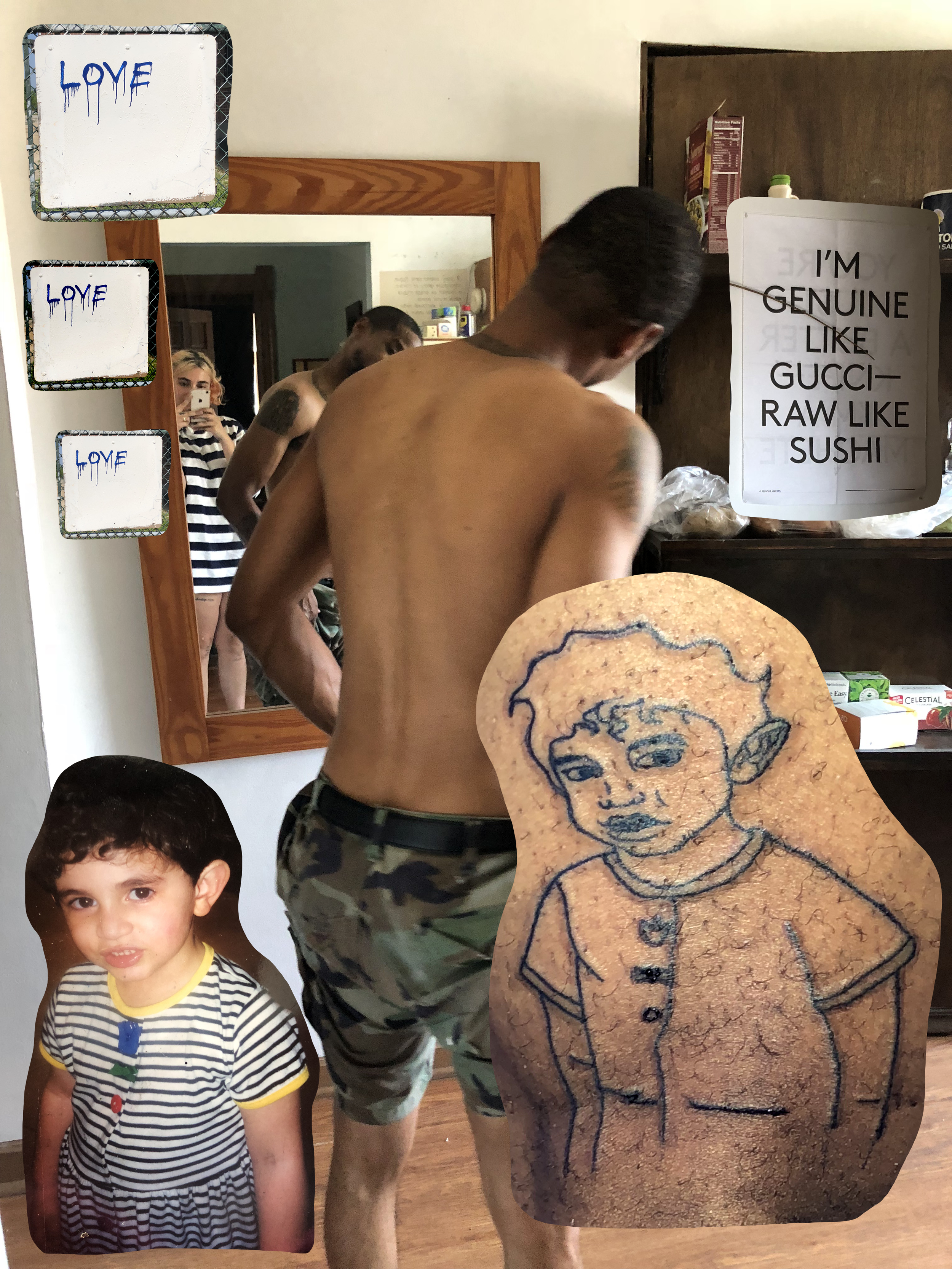

Local, Hava Toobian (2019). Paintings material: shaped MDF wood, acrylic, photography, appropriated images, found/stolen objects, and cloth.

Transcript: I have this show representing my interests in diaspora and specifically queer diasporic theory and critique. And having this show be a representation of my experience specifically as a Jewish Iranian Kurdish woman in the U.S. and how my upbringing and family dynamics have so much to do with the way that I visually take in information and how I visually accept and adapt information and objects into a context that is authentic.

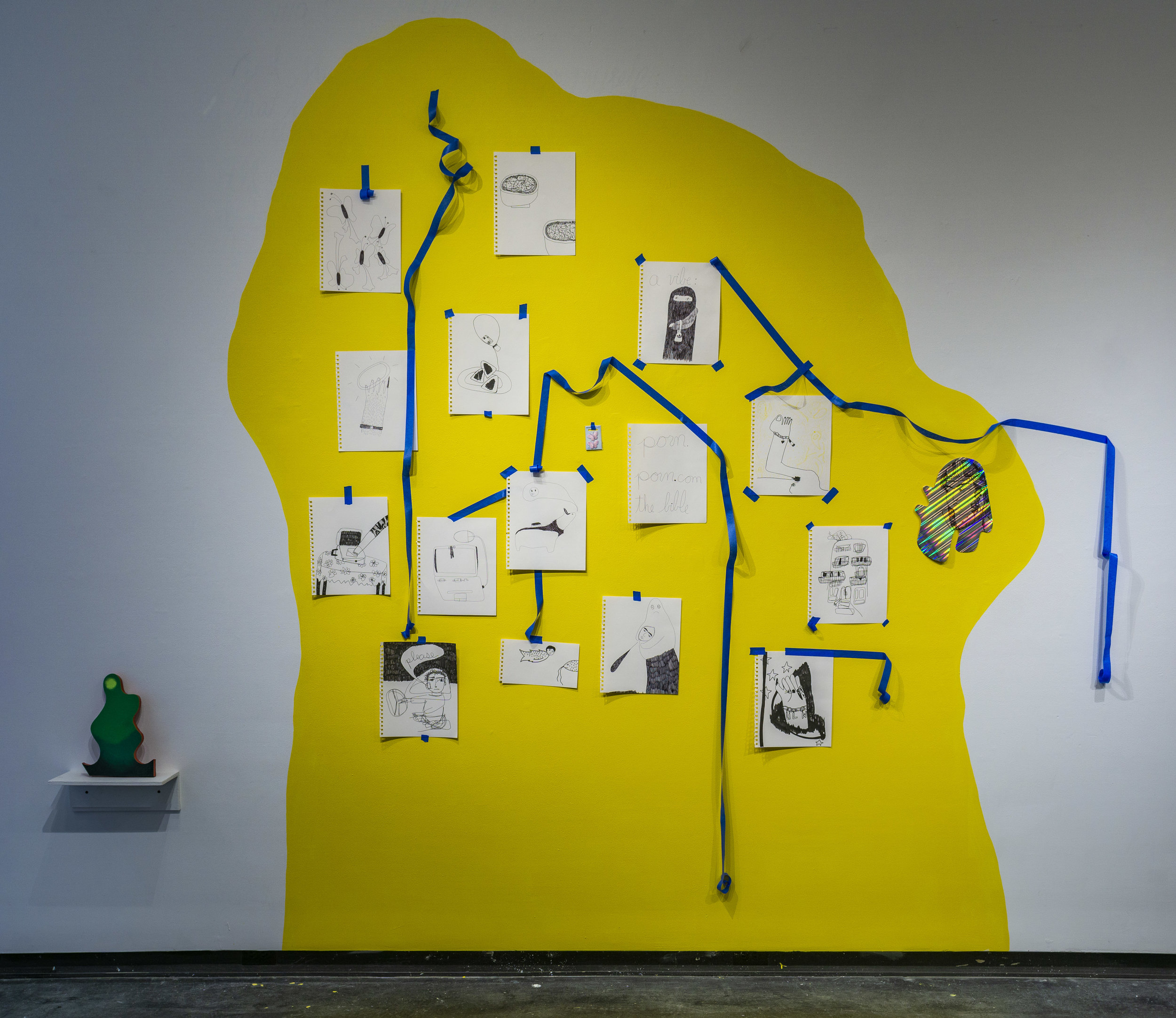

In this show, I am mostly interested in sort of a time and space binary when talking about a diasporic person in the U.S. There is this spatiality of ‘where is this person’s homeland?’ Which is one way of thinking of the diasporic person, which is very limiting and really does curtail their ability to adapt in their newfound spaces and becomes a very nation-state way of thinking of the diasporic person. I am also interested in a time binary, meaning, how does the upbringings and how does ancestry and how does genealogy, geology, how do all these things incorporate into a singular body? How do they adapt into the world, into their current states, into their current homes and place-makings? Having a queer understanding of home and belonging has more to do with context relations that are current and not in the past.

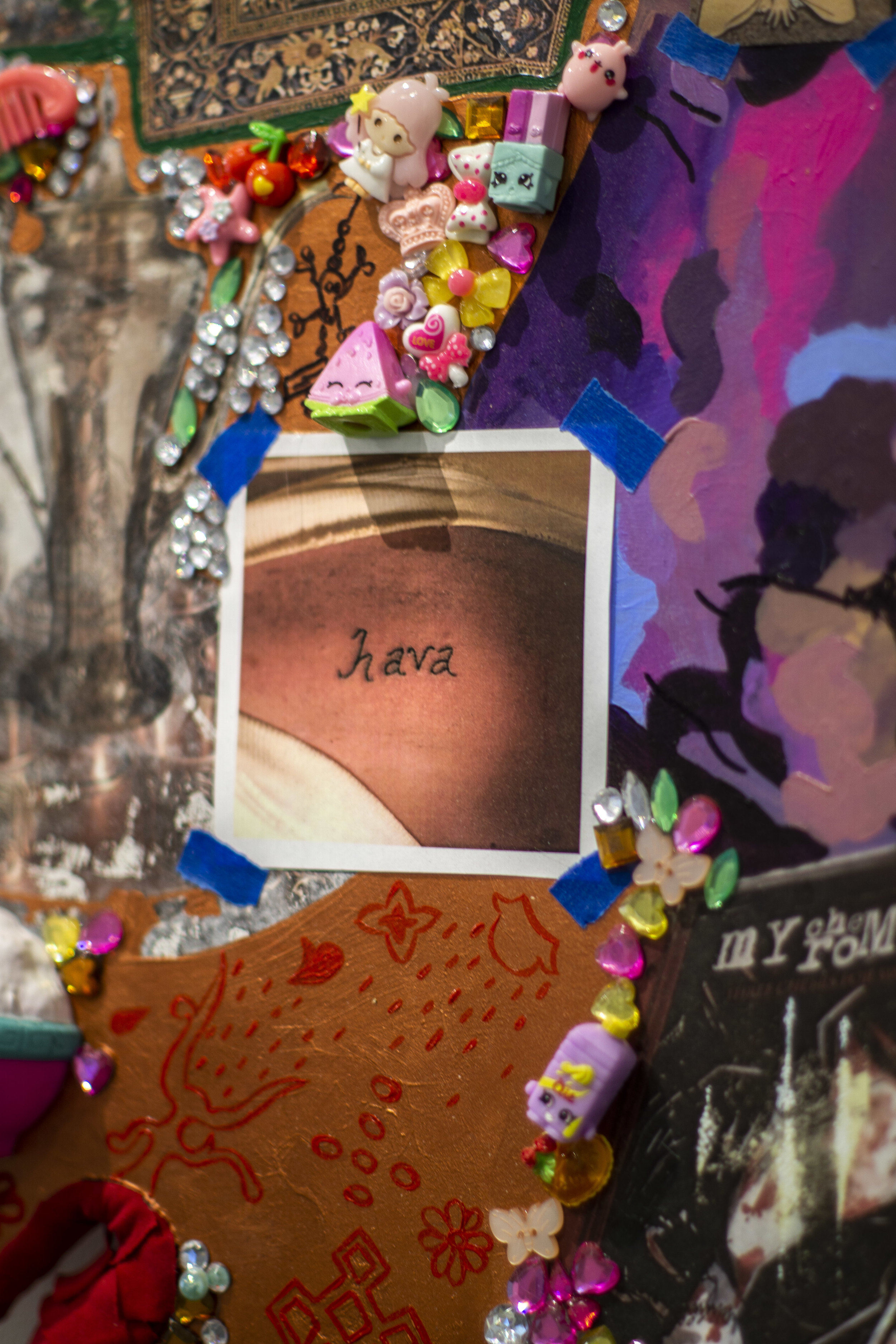

I have all these childhood photos that my dad gave me and I carry them around and offer them, or even my name, some people have my name tattooed on their body. In the ways that I’ve seen other artists archiving their childhood has been precious and has been true to its original state and something that interests me, in terms of home and belonging and my entire show, is the preciousness of the current experience and not the preciousness of the past in archive.

So, having the generous contributor that donates their time and body to my art practice in this specific series of experiment or performance, or however it is you take it, allows the other person to have agency in this whole process. Where they’re not only changing the context of my childhood photos and my name, because I have no control over where these bodies may end up and the canvas itself and the medium itself has so many variables in the places it can be.

Those ideas of home and belonging in a queering aspect and what I’m interested in, in this queering idea of home and belonging, has a relationship to reinventing a space and redefining a spatiality. If I understand a queer diasporics person as someone who time and time again has to recreate a home, then place-making is a reoccurring aspect of people’s lives, especially for the queer diasporic person. So, having me and my body be represented in ways that I can’t control as I do in everyday life, but as a performance piece is interesting to me and speaks a lot to how I feel about my place-making in the world. How does history and how do bodies and people interact with consumable imagery? And how do these visual signifiers interact with consumability? Those things are extremely related to me because it’s what’s given to us and it is assigned to what can we be interacting with.

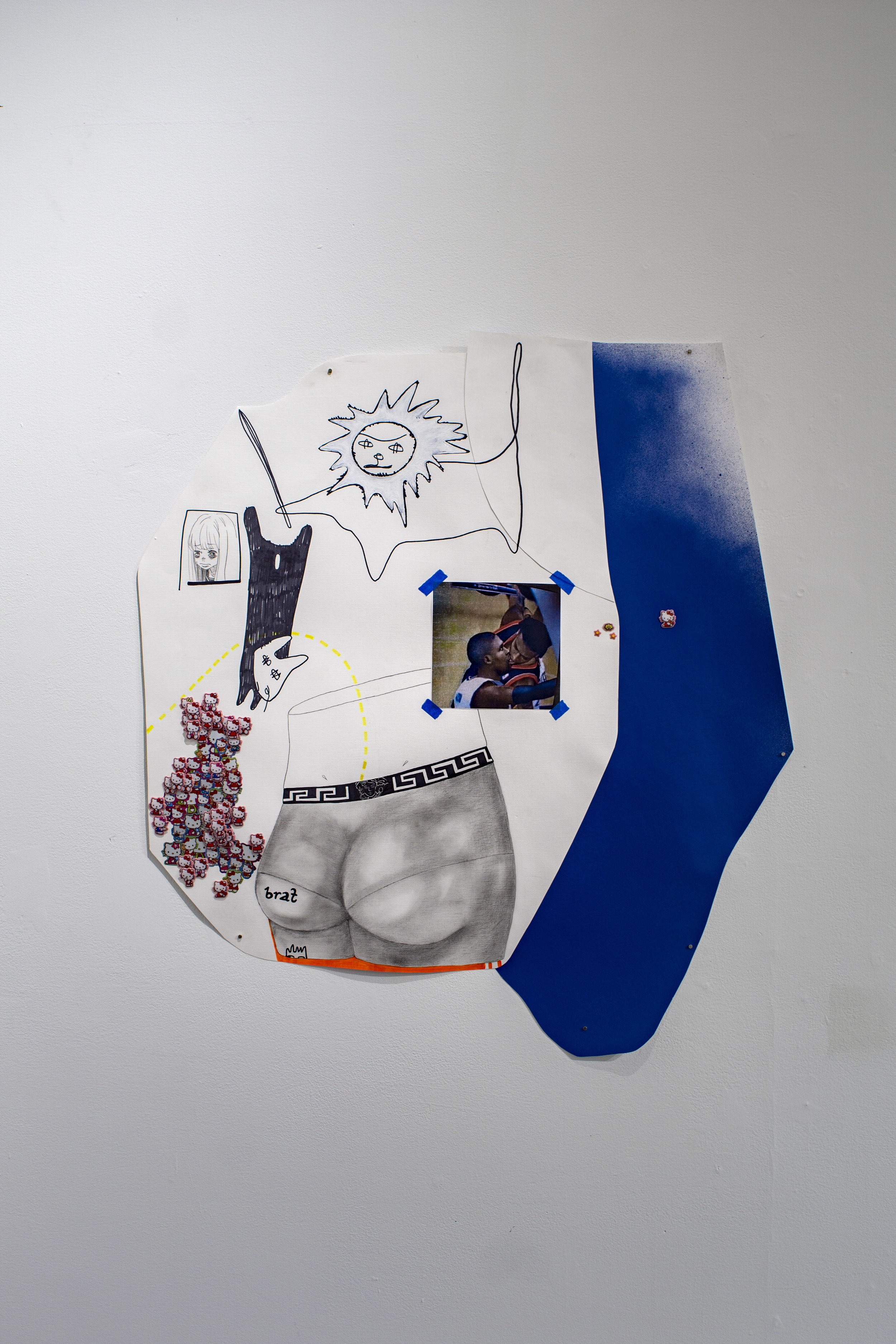

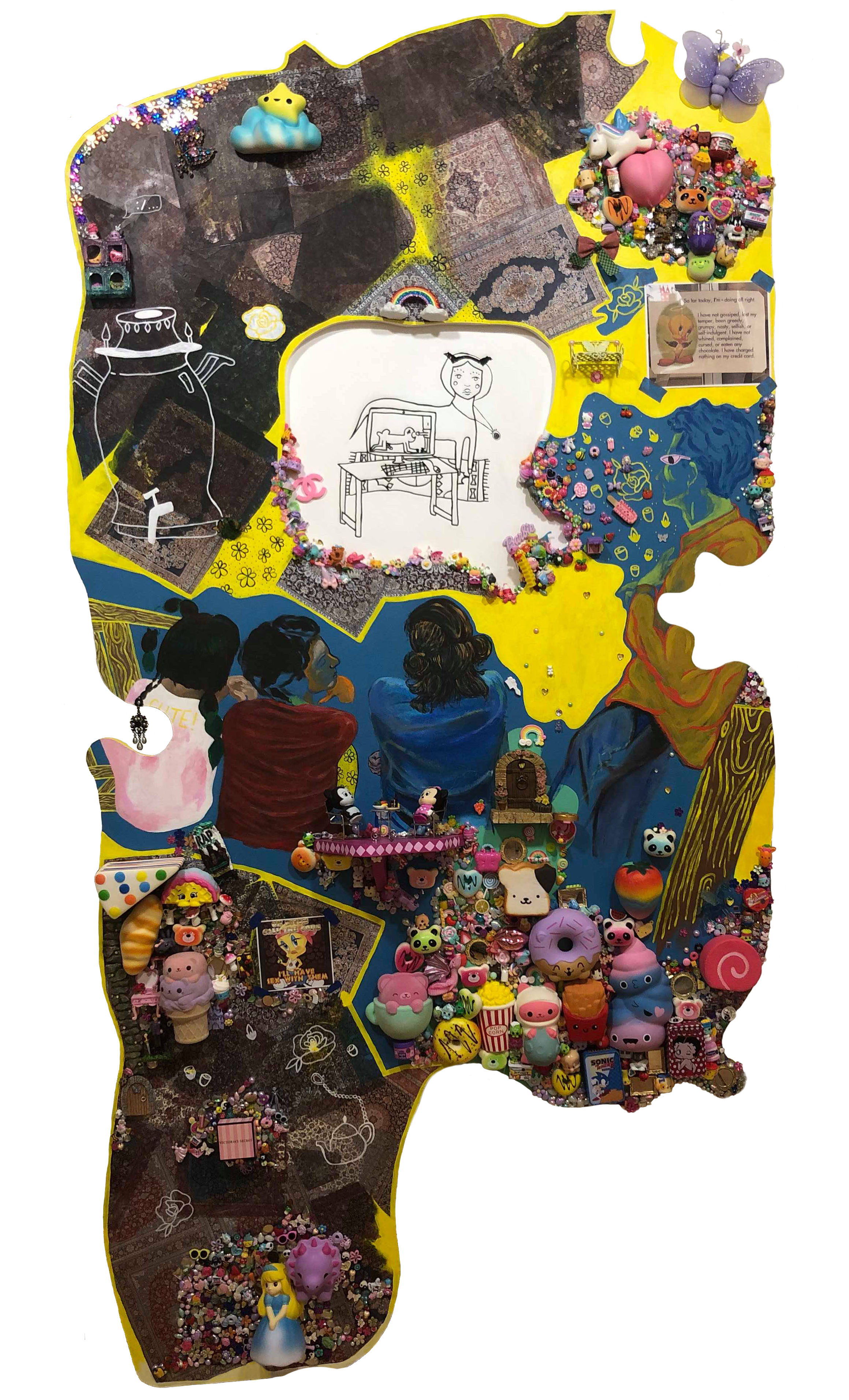

I Wish Misty Was Still in Pokemon, Hava Toobian (2019). Paintings material: shaped MDF wood, acrylic, photography, appropriated images, found/stolen objects, and cloth.

The way that I use my paintings is that I have these visual signifiers from multiple areas of what I either see as diasporic or I see as current pop-culture and the way that they do interact are just physically being put onto the canvas and having the fluidity of the shape of the canvas and the fluidity of the images of the Persian rugs and the images of family members and the images of Tweety Bird. Those things interact together for me and my body and for multiple queer diasporic peoples body. Even if they don’t understand the Iranian-ness or the Jewish-ness or the Kurdish-ness, their diasporic-ness allows them to understand this fluid intermingling of the ways that their stimulating their multiple selves.

I see how my parents have shown me all their Persian art, anything that they brought home from Iran or anything that they find in the Iranian supermarkets where I grew up in Dallas. Those things have this certain aesthetic that ‘more is more!’ You put things on, things are beautiful and lavish and gold or red. I see my art as something that my friends look at and say that they can connect with it, even if they don’t have access to understanding diasporic-ness, because some of them do come from Anglo-Euro backgrounds. That doesn’t mean that they are able to access every single part of it, not everything is accessible, not everything is understandable, but the ways that I find my authentic self and the ways that queer artists may find their authentic selves is touching on the multiplicities.

My Iranian-ness comes from the U.S., specifically the Dallas Persian community, the Dallas Persian Jewish community that I grew up in. So my color choices, my aesthetic choices, in those ways should personally and in the way that I’m thinking of my art-making should speak to that community of Iranian-ness.

One of my videos, ‘I Need to Call my Brother’ has the concept of trans-languaging in it. Where my father has to call his brother who currently lives in Jerusalem and he has to use a phone card that has the language hebrew in it. He is speaking to his siblings in Farsi and he is talking to himself or me who is filming him in English. Those interactions, to me, is where my home lies, because there’s no physical space where I’m gonna have all those places interact all at once, all the time. It’s in these experiences where my home and belonging is.

Hava Toobian: "Both of my parents are Jewish from Iran, but I was born in the U.S. and went through a Jewish day school for most of my life, and that's really prevalent in my life. There were often conflicts at the Jewish day school because of my Persian identity. Once I left it was even more complicated because not only am I a Persian living in the U.S., but amongst the Persian community sometimes it matters and sometimes it doesn't matter that I'm Jewish. It gets overly complicated because there is no one way to exist. Nothing works in that way with identity. I go to Israel a lot and there are a lot of ways I feel very at home in Israel but it's complicated because of the way that I feel around occupied territories, and family relations. In the U.S. I feel at home when I'm with my family but there are some obvious conflicts that occur with that, especially growing up in Texas."

Filming: Hava Toobian and William Chen

On-Set Help: Veronica Sherman

Video Editing: Hava Toobian and Ian Grant

Transcription: Ben Rejali