The Question of Solidarity: #BlackOutTuesday and Radio Alhara

by Samuel Tafreshi

“How do you connect solidarities together in a way that makes it organic, that makes it contextualized, and also makes it true?” - Yazan Khalili, Radio Alhara

These are the questions the hosts of Radio Alhara asked as they debated whether or not to broadcast on #BlackOutTuesday and how best to show solidarity with the ongoing struggle for Black liberation in the US happening in the wake of the brutal police murders of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor.

Radio Alhara, an online radio station broadcasting from Palestine, was responding to a call for music platforms and radio stations to go silent on Tuesday, June 2nd in order “to hold the [music] industry at large, including major corporations + their partners who benefit from the effort, struggles, and successes of Black people accountable.” The action was initially promoted by Jamila Thomas and Brianna Agyemang, two Black women working in the US music industry, as #TheShowMustBePaused, but transformed into #BlackOutTuesday as it gained momentum among celebrities and corporations.

As Spotify, Apple Music, and MTV each observed some version of the media blackout and black squares flooded Instagram in a symbolic, and in many cases performative, display of solidarity on Tuesday, Radio Alhara decided to go an alternative route. Rather than cease broadcasting for the day or release a statement, they changed all of their programmings to broadcast the speeches of Black activists and intellectuals, excerpts of interviews, and music related to the Black Power movement. On a day when most cultural institutions chose to show solidarity through silence, Radio Alhara wanted to be loud.

On Thursday, June 4th, Khabar Keslan had an opportunity to sit down virtually with three of Radio Alhara’s founders, Yousef Anastas, Elias Anastas, and Yazan Khalili, to discuss the decision to broadcast during the media blackout, anti-Blackness within the Arab world, and how to meaningfully connect solidarities. As we spoke, Yousef and Elias were talking to us from Bethlehem, Yazan from Ramallah, and myself and Omar Alhashani, from Beirut and Jeddah respectively.

***

Radio Alhara has drawn a diverse array of DJs, musicians, record collectors, and writers into its community of contributors and listeners in the months since its creation. “The name relates quite well to the concept and projects,” Elias Anastas explains. “It’s the hara, which means the neighborhood, and we’re trying to say that the entire world can be a neighborhood.” While bringing in contributors from all over the world, Radio Alhara has sought to create a ‘communal radio,’ one that is “coming out of the community, for the community… very much anchored to the local community.”

This community-focused structure is at the very heart of the station’s ethos. “The whole idea of the radio is not to do things in a pre-formatted way... If you follow the radio you’ll see that the majority of things that are aired are not experimental in the content sense; it’s in the way the radio is being structured.”

As Yazan Khalili puts it, Radio Alhara is exploring “how to produce a radio—a space—politically through the connections and the structure, the community, and the producers rather than the listeners.” While Radio Alhara has been challenging traditional networks of broadcasting, #BlackOutTuesday compelled them to reflect on and further develop the way they’ve been producing content so they could engage with their audience and community on a different level.

Most importantly, the station wanted to show solidarity in a way that fit their context and their overall philosophy. “It’s how to use this space, how to use this platform, and how to use this sound that was coming out from the radio to connect to the community,” says Yazan. “I wouldn’t say that we disagree with the act of blacking out. It works in its context. The question is how do we, what do we do to show solidarity through our context?”

**

“At the beginning,” explains Yousef Anastas, “we thought of doing the blackout and turning off the radio, doing a statement, etcetera. But then we had a discussion between us and we tried to see what made more sense for the radio.”

Simply put, going dark felt counter-productive for Radio Alhara. “In the frame of #BlackOutTuesday,” Elias notes, “us going silent or turning off the radio for a day was basically closing down the public space. The idea was that instead of being silent, we wanted to be loud.”

“We had a very long discussion,” Yazan continues. “You know: ‘This is coming from Palestine. How do we show solidarity? What does it mean in a political way to show solidarity and should we also bring up the issue of Palestine in the discussion?’ Like all these essential political issues. How do you connect solidarities together in a way that makes it organic, that makes it contextualized, and also makes it true?”

“In our part of the region, there’s a lot of racism. There’s a lot of racism in general, but racism towards Black people is super present in the Arab world… It was maybe more ‘‘efficient’’ to broadcast some stuff that was related to the Black Power movement--rather than just blacking out and making a sort of buzz on social media,” Yousef concludes. “No posts, no announcement, no nothing; but the content of the entire radio was changed.”

**

This excerpt from a 1989 interview with James Baldwin played between sets throughout the evening:

What is it you want me to reconcile myself to? I was born here almost sixty years ago. I’m not gonna live another sixty years. You always told me it takes time. It’s taken my father’s time, my mother’s time, my uncle’s time, my brothers and my sisters time, my nieces’ and my nephews’ time. How much time do you want… for your ‘progress’?

In place of the scheduled broadcast on Tuesday, Radio Alhara’s listeners tuned into the speeches of Angela Davis and the music of Gil Scott-Heron. Radio Alhara’s signature jingles and regular announcements were replaced by excerpts from interviews.

“This material is not new to us, ya3ni, it’s something that I think we grew politically with,” Yazan notes. “The speeches of James Baldwin, of Malcolm X, of Angela Davis, of Stokely Carmichael, the Black Power movement, the roots of Hip Hop through the Last Poets and Gil Scott-Heron; it wasn’t hard to imagine what to broadcast.”

“We also went to a certain history in the Black Power movement,” he continues, “back to the roots of the movement in the 60s and early 70s where it was about creating the community, the collective to take care of each other, because we think now there is a kind of a return to that moment.”

**

Despite changing the bulk of their programming on #BlackOutTuesday, Radio Alhara still chose not to release any explicit statement expressing solidarity or explaining their broadcasting decisions. Instead, the goal of the programming was to bring lots of elements together and have them gradually accumulate on top of each other to “make their own statement,” as Yazan says.

The members of Radio Alhara explain that this was in part because they feel the expressions of solidarity released by cultural institutions often ring disingenuous and superficial. Rather than state solidarity, Radio Alhara wanted to engage in an act that could begin a conversation on racism in the region and allow them to connect with their community through the Black struggle in America.

Yousef also notes that the context of Radio Alhara in Palestine is different than in other countries and this necessarily affected its response to the media blackout. “In our context, we have a lot of situations where you have a martyr, you have something that happens and the first thing is that all of the cultural scene mourns and the systematic mourning of these events becomes a bit… because it’s systematic it becomes a bit…”

“Hypocritical?” Yazan offers.

“Yeah!” Yousef agrees. “So I think that the way we responded to that event [the murders of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor], in our context, is also a way to respond to what happens usually when an event like that happens in our part of the world. Don’t just close down and mourn and respect in sort of a passive way” Yousef recommends, “but be more proactive and have something to say.”

“After we responded to #BlackOutTuesday, I didn’t think of it before, but [changing the programming] was a nice way of reacting to what was happening with the Black Power movement, but also to the way we respond to these kinds of events locally.”

“Historically, the cultural scene wasn’t always--especially in Palestine--put in the background of what was happening politically, in the context of the struggle. The cultural scene was part of the struggle. Today, because of too much respect or too much mourning, the cultural scene has moved to the background of the struggle; there’s a sort of a separation.”

**

Radio Alhara’s response to #BlackOutTuesday was an experiment in solidarity. What does it mean to show and act in solidarity, and how can you form connections between your comrade’s struggle and your own locality? Radio Alhara confronts the question of how to meaningfully act and respond when you see other oppressed peoples gaining the momentum of rebellion and organized resistance.

“A friend was once saying,” as Yazan paraphrases, “that the moment of solidarity is a moment of understanding your defeat, your collective defeat. It doesn’t come from a moment of strength. It comes from a moment where you are aware that we, the Palestinians, the Black people in America, the jiniss in other places, are all in a very weak, very defeated moment where we need to stand up together to stop this. To be able to rise up again, somehow together.”

Yazan argues that the Palestinian struggle has not yet reached “the moment of eruption” that the Black struggle in the US has, and that this moment of solidarity “comes from an understanding of the failure and the defeat of the Palestinian struggle and the oppression that we are still living in.”

“The Black struggle in America connects not only to Palestine, but to any community that is under oppression and dealing with injustice; how do you see your future through their eruption? How do you see that moment of moving, of acting, of collectivity, of violence as well! Violence is not a bad word when it’s used against systematic violence.”

“There is always systematic violence in the US, in Palestine, but the question is,” he continues, “being aware of the oppression you are living under: what do you do when you see your comrade reaching that tipping point? How do you, through that moment, seize it and make your community aware of your comrades’ moment so that your community becomes able to imagine its eruption in the future?”

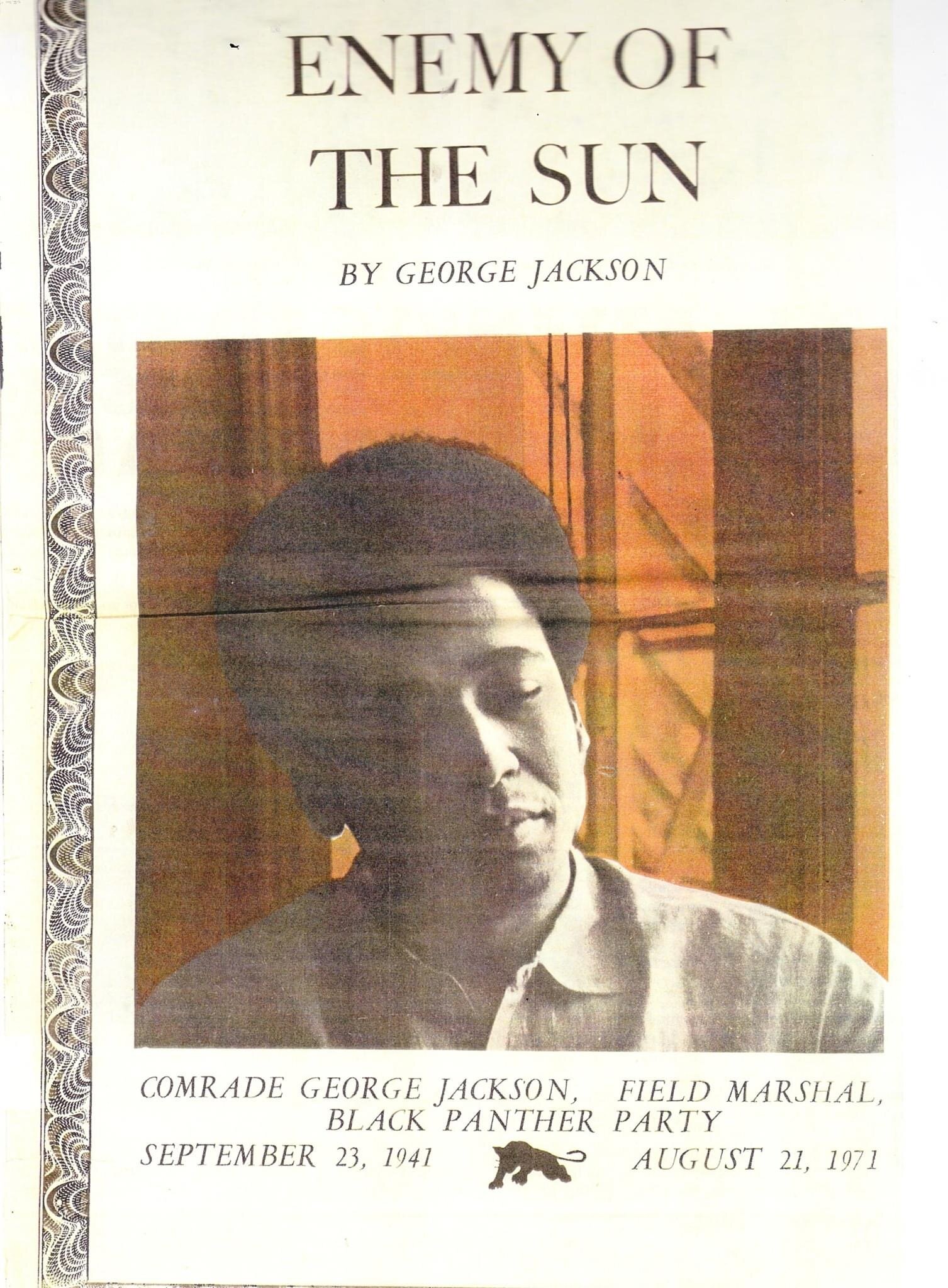

“No Palestinian went to fight in America with the Black Power movement, neither did the Black Panthers come to Palestine,” claims Yazan. “But in a cultural way, they were connecting all the time… This history is very much also part of our history.” Yazan points to the “beautiful story of the poem they found in George Jackson’s cell after he was killed.”

The poem was written in Arabic by Palestinian poet Samih al Qasim and published in English as Enemy of the Sun by radical Black publisher Drum and Spear Press as part of the first anthology of Palestinian poetry in the US. Following the murder of author and Black Panther, George Jackson, by prison authorities in 1971, two poems were found scrawled on a piece of paper in his cell. Both poems were posthumously published by the Black Panther Party newspaper under a single title, Enemy of the Sun. The poem was printed and distributed as the work of George Jackson until it was revealed in 2009 that Jackson’s personal library held an anthology of Palestinian poetry containing Samih al Qasim’s poems, Enemy of the Sun and I Defy.

Jackson had handwritten copies of Qasim’s poems in his prison cell and it was an accident of true solidarity that Qasim’s poetry enjoyed forty years as poetry of the Black Power movement under Jackson’s name. “Enemy of the Sun,” Yazan contends, “shows you how these two struggles were connecting always, even in a subtle way.”

Special thanks to the Radio Alhara team.

Samuel Tafreshi is an Iranian-American writer based in Beirut, Lebanon. He holds a BA in Religion and is currently pursuing a graduate degree at AUB. His work has been published by Khabar Keslan and Ajam Media Collective. A forthcoming piece will be featured in the next issue of Rusted Radishes.