"It's Crowded and There is No Mercy!"

by Mariam Elba

This work appears in Khabar Keslan Issue 1. DISORIENT

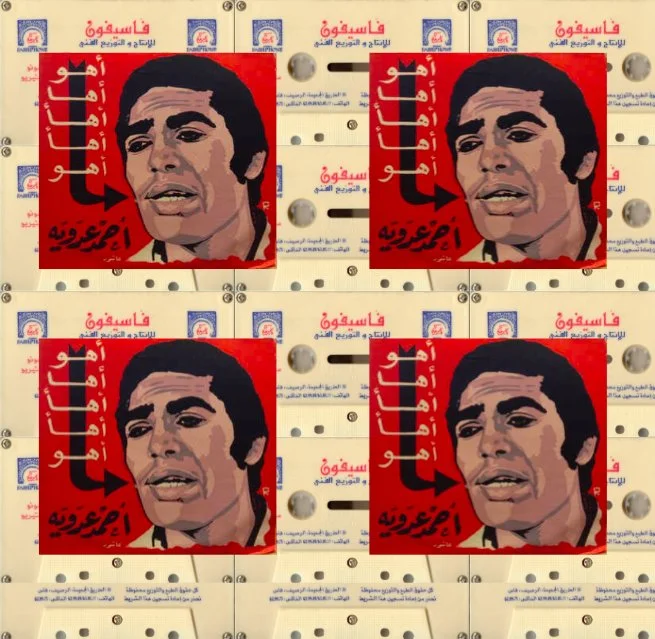

Original artwork by Yasmine

Sha'abi music disavows a unitary Egypt

“I wonder about this age

That puts some on the shore

And others are lost at sea

Who have seen torture and agony

And there are the ghalaba [1] who

Receive their share through the eye of a needle…

Those who are satisfied push the hungry…

There are those who drink honey

And there are those who drink bitterness!” [2]

—Ahmed Adawiya. ‘agaby ‘aleik Ya Zaman. Ahmed Adawiya. Maamoum El Shennawi, 1975

In the early 1970s, Ahmed Adawiya came out with one of his first hit songs, “Zahma Ya Dunya Zahma,” or “It’s Crowded, Everywhere is Crowded,” produced by Sawt Al Hob on cassette tape, and sold in marketplaces in sha’abi—lower, working class—neighborhoods. Millions of Adawiya’s cassettes were reportedly sold as he rose to popularity.[3] His music was unlike any other mainstream artist’s at the time: he used colloquial slang and sung in a boisterous style considered gauche by the country’s elite. His first hit song was an anthem to the urban experience in Cairo during a period of immense change: the economic policies of the infitah, Egypt’s economic “opening” to private foreign investment were being enacted; the 1973 October war with Israel was raging; and masses of rural migrants were settling into urban centers, straining cities. Adawiya’s rise coincided with then-President Sadat’s economic liberalization policies that exacerbated socioeconomic inequality, including the weakening of the public sector; IMF borrowing and the consequential decline in the standard of living; lack of labor regulations, and labor unrest. Before Adawiya himself appeared in the 1980 film Shaaban Below Zero singing “Zahma Ya Dunya Zahma,” it was already a staple heard in taxi cabs, marketplaces, and—across the country—those apartments lucky enough to have cassette players.

“Zahma Ya Dunya Zahma” is a catchy, upbeat song about navigating crowds and traffic to make an appointment on time. The song was popular among youth at the time, and when it was sung in Shaaban Below Zero, Adawiya was accompanied by a belly dancer. Although set to a light melody, the lyrics describe a harsh reality of being a resident in a populated, urban area with insufficient services:

Zahma ya dunya zahma

(It’s crowded, everywhere is crowded)

Zahma we taho el habayeb

(It’s crowded and our loved ones are missing)

Zahma wala ‘adsh rahma

(It’s crowded and there is no mercy)

Moulid we sahbo ghayeb

(It’s a saint’s festival and the saint is missing) [4]

Adawiya’s song lyrics depict the frustrations that arose in Egypt's burgeoning urban areas: traffic became a common headache, and public transportation was inadequate. These failures became part and parcel of the Egyptian urban experience, and the song served as an anthem to the unfulfilled promises of Egyptian nationalism.

Ahmed Adawiya is considered the first of dozens of artists from the lower working class to reimagine the genre of sha’abi music. This new sha’abi music shocked many listeners with its break from tradition, gaining a large following as it spoke to the socioeconomic conditions of the period. Common themes in popular sha’abi songs included not only the usual tales of love and longing but also of frustration and despair, addressing poverty, economic disparity, and inequality in contemporary Egyptian life. On top of that, these songs were performed in very localized, colloquial Egyptian dialects of Arabic, unheard of at the time for more formal Egyptian music and films. This in part reflected the artists and audience—it was members of the urban working class who were creating this music, and they were singing for sha’abi communities.

Several factors in this period can help explain the prevailing themes of despair over injustice and inequality evident in these songs. Scholars have cited the frustration following the abject failure of Egypt and the Arab states in the 1967 war with Israel; the letdown of Arab socialism under Nasser and the subsequent stumbling of “de-Nasserization,” and the infitah instituted by Sadat as catalyzing the birth of this musical genre.[5] Sha’abi songs‘ main lyrical themes of socioeconomic frustration and economic inequality, articulated in colloquial dialects considered vulgar by cultural elite, convey important realities that the period‘s subaltern Egyptian working class communities experienced—realities that, before this time, were not addressed in popular cultural expressions of Egyptianness. With the arrival of the cassette tape and the relative ease of making pirated copies, it was introduced to larger public discourse.

Cultural production for and about the sha'ab before the 1970s

Pop music in Egypt existed before sha’abi music, although it served a different purpose. Defining national cultural heritage in popular culture has historically been central in forging Egyptian national identity, both pre-British independence and during the Arab nationalist era that began with Gamal Abdel Nasser’s presidency. At the turn of the twentieth century, knowing Egyptian colloquial dialect became essential for broad public consumption of printed media, political cartoons and commentary, theatrical productions, nationalist songs, and folklore. To foster a cohesive national identity, according to Ziad Fahmy, “these [nationalist] ideas had to be reworked, reconstructed, and transformed into a form that was meaningful to local Egyptian milieux, and equally, they had to be in a language everyone understood.”[6] Distributing forms of mass media outlined a national identity in which one of the focal points was the use of Egyptian colloquial—particularly the Cairene—dialect. These initial idiomatic cultural expressions espoused a unified Egyptian national identity, what it meant to be Egyptian while the country was occupied by Britain, and has further developed its identity in the years after independence.

As the radio became a “central institution in Cairo’s musical life,”[7] many of the Egyptian radio stations that emerged in the 1920s were subsequently nationalized in the 1930s. During the Nasser era, music and cinema often centered themes around what it means to be Egyptian, and featured forms of Egyptianness that were perceived to be “modern,” thus complementing modernizing state projects like the Aswan Dam and the nationalization of the Suez Canal. As sha’abi music rose to popularity in the 1970s, it spoke against the empty promises of Egyptian nationalism and modernism, the failures of which were painfully obvious to urban dwellers living in poverty. In this sense, sha’abi music was an anti-modernist cultural expression of Egyptianness by the urban working class—a demographic that was either denigrated, obscured, or romanticized, depending on previous expressions of nationalist identity.

As far back as the late nineteenth-century, awlad al balad—“sons of the nation,” the sha’ab’s precursor—had had a negative perception in high Egyptian public discourse, although this began to change in post-1952 Egypt. The concept of awlad al balad carried different, context-dependent meanings. In nationalist discourse, awlad al balad was at the forefront of formulating an “authentic” Egyptianness. On another level, awlad balad also connoted an unruly, uneducated population of ghalaba—those who do not know better. The paradoxical glorification of the indigenous, working Egyptian, both rural and urban, under Nasser’s reign was the base of the nationalist narrative of building an independent, self-sufficient nation. This classist lens of viewing awlad al balad continued into Sadat’s rule: it could mean native Egyptian identity in some contexts, particularly when the state attempted to conjure nationalist sentiment by appealing to the lower classes; in others, the uneducated unruly masses that used coarse language. Sha’abi music, along with the communities that produced it, was looked down on by producers of high culture, e.g., music and film created within the centralized, regulated apparatus of the state which had certain ideas about sophistication and what music should and should not be. One only needs to compare some of Umm Kulthum’s most well-known songs, in standarized Cairene dialect with sophisticated lyrics addressing traditional themes of loss, to the socioeconomic issues brought to the fore.

The infitah, sha'abi identity, and cultural production

Adawiya’s music, and sha’abi music more broadly, also coincided with the proliferation of portable music players, cassettes, and the decentralization of institutions that produced popular culture. A university student in 1977 living in Roushdy, a middle-class neighborhood in Alexandria, recalled playing Ahmed Adawiya songs on her cassette player even though her elderly neighbor chided her, believing it to be too base for a student in the prestigious field of engineering. But while the music was initially considered too low-class for radio, by the late 1970s, large cross sections of urban Egypt had heard of Ahmed Adawiya and were likely to have listened to his music in a market or taxi.

Several factors led to the spread of sha’abi music. In Egypt, the Stalled Society, Hamied Ansari shows that the infitah “gave rise to a nouveau riche… consisting of middlemen, commission agents, and comprador merchants who thrived off of imported goods.”[8] The increasingly visible wealth of this small, elite class accentuated economic inequality for the urban working class. Other elements of “de-Nasserization”—particularly land de-sequestration beginning in the early 1970s concurrently with the infitah—significantly contributed to placating the elites and further alienating the lower classes.[8] A new capitalist class emerged among the country’s elite that was strongly connected to the government. As Tarek Osman notes, “the regime used the new economic opportunities to build its own power base to reward its cronies and allies.”[9]

This process was not without strife: workers’ unions across the country rebelled against the state’s refusal to accommodate the increased cost of living, and steelworkers in Helwan and textile workers in Alexandria held strikes in the mid-1970s. The state later impounded funds of the largest union in the country, the General Union of Egyptian Workers, as a way to subdue worker unrest. Even public institutions became increasingly marginalized, leaving educated workers with meager salaries and a stagnant public sector.[10] This economic malaise culminated in the Food Riots of 1977, a nationwide uprising in cities against the proposed cuts to food subsidies. This social and economic exclusion became a significant part of public consciousness, and it was evident not only in sha’abi music but in popular films and TV series that attracted scores of viewers.[11] The state’s economic policies were failing the vast majority of Egyptians, creating a space—previously absent in formal cultural production—for alternative expressions of Egyptianness and the experience of being an urban, working class Egyptian to proliferate.

The music industry was becoming increasingly decentralized as a result of the Sadat’s open door reforms. The proliferation of the cassette tape and cassette player made sha’abi songs incredibly accessible and were played in taxis, microbuses, and market stalls in working-class neighborhoods. With the ease of duplicating copies of cassette tapes with two-cassette players, making several copies to distribute was common. The cassette tape was a cheap medium to record and distribute sha’abi music to consumers since it made music increasingly portable and easy to acquire. Sha’abi music in this era was the background of a working-class commuter’s soundscape in their daily ride in a microbus, taxi, or when running errands at the market. Consumers could increasingly relate to the experiences they heard in these everyday ventures.

Even as Egyptians from various social groups were consuming this music, the negative association with the lower working class dancing to such music at weddings and festivals endured. Music produced from within is backward, unsophisticated, and “inauthentic” Egyptian music. Both in terms of distribution and in some of the prevailing themes of the experiences of inequality and despair, the infitah catalyzed changes in cultural production amid increasing inflation, the gradual erasure of the middle class, and a widening gap between the elite and lower classes.

The Sha'abi Represent Themselves

By the 1990s, sha’abi-produced culture had become more acceptable, and sha’abi artists like Hakim were broadcasted on Egyptian TV and radio. The change in pop culture continues in Egypt, as accessibility to media—both consumption and creation—has increased drastically since the 1970s, giving rise to a new type of sha’abi music.

Today’s techno-sha’abi music—or mahraganat as it is popularly called, referencing music played at festivals and weddings—is reminiscent of Western rap and techno. It bears a strong presence of autotune. The slang employed by today’s sha’abi singers is even deeper than that of its musical precursors. Producing music is even easier, outdoing the impact of the cassette tape, as artists use pirated software and can find beats for free on the internet; easily upload songs on YouTube and SoundCloud, and share them on social media—all of which have contributed to grassroots distribution networks for a sha’abi music.

As with its sha’abi predecessor, the elite often chides mahraganat for being profane, lewd, and, in short, only fit for the lower class. Many popular songs do indeed have themes that are too profane, and sometimes too sexually explicit, for the radio. They also include more overt sociopolitical undertones increasingly, often speaking against the way that they speak against state discourses about the lower class. For instance, Sadat and Fifty, two of the first popular mahragan artists as the genre was emerging a few years ago, released songs that spoke to the experience of lower, working-class Egyptian while dispelling common stereotypes. In one song, they speak out against sexual harassment and patriarchal norms with lyrics like “masculinity is up to me.” Asserting masculinity, and what it means to be a working-class Egyptian man, is a common theme in mahraganat.

In one of the most potent examples of this, Sadat, “3laa2 Fifty,” and “Felo” collaborated in 2014 to release the song “Ana” or “Me.” They sing, “I am the kid in the alley, I am ‘culture’ and ‘civilization,’ I am the kid who is throwing a toob from the highest floor of my apartment building. I am the son of factory-workers. I am a ‘lost cause,’ a loser.” They juxtapose buzzwords often used in nationalistic state discourses—”culture,” “civilization”—with “son of factory workers.” They reclaim familiar refrains in which the Egyptian state blames the lower classes for economic stagnation, political instability, and lack of public safety.

Now more than ever, sha’abi music is a mode of expression, not only in an overtly political sense but also in the lived experience of the marginalized working class. This is one of the ways working-class Egyptians have long been exercising their own agency. Even as their music has begun to be been co-opted by mainstream pop culture, local sha’abi artists continue the legacy that Ahmed Adawiya started: expressing themselves on their own terms, and harnessing the DIY and grassroots ethics of their sha’abi forebearers.

Mariam Elba is co-editor for Muftah’s Egypt and North Africa pages. Mariam is a New York-based, Egyptian American freelance writer covering grassroots initiatives, popular media, and cultural representation in American Muslim communities and in the Middle East, particularly in Egypt. She has bylines in The Nation, PolicyMic, Waging Nonviolence, Truthout, and Muftah. Mariam holds a BA in English and History from CUNY Baruch College and a MA in Journalism and Near Eastern Studies at NYU. She has written about emerging social infrastructures in public transportation in urban Egypt and the history of modern sha’abi (popular, working class) music in Egypt, as well as the material conditions in which it emerged. Mariam hopes to continue writing on everyday trends among marginalized and disenfranchised populations in the Middle East and the United States.

Footnotes

- This is an adjective in Egyptian Arabic that does not only mean “poor” in the material sense, but also powerless, disenfranchised, unable to help themselves. This term is often used to refer to the working poor.

- Ahmed Adawiya. 'agaby 'aleik Ya Zaman. Ahmed Adawiya. Maamoum El Shennawi, 1975? Accessed May 02, 2016. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5YjV_WEcf9I; this mawwal was sung by Adawiya towards the end of the film Shaaban Below Zero, which considered by many to be a commentary on growing discontent with increasing social and economic inequality

- James Grippo. "What's Not on the Radio! Locating the ‘popular’ in Egyptian Sha‘bi." In Music and Media in the Arab World, edited by Michael Frishkopf, 137-60. Cairo: American University in Cairo Press, 2010. 153.

- Ahmed Adawiya. Zahma Ya Dunya Zahma. By Hany Shenouda and Hassan Abu Etman. Ahmed Adawiya. Maamoun El Shennawi, 1973(?). Accessed May 2, 2016. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=djqFU71juWM.

- Magdi Wahba. 1972. Cultural policy in Egypt. Paris: UNESCO.

- Ziad Fahmy. Ordinary Egyptians: Creating the Modern Nation through Popular Culture. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2011. xii.

- Salwa El-Shawan. "The Socio-Political Context of Al-musika Al-arabiyyaii in Cairo, Egypt: Policies, Patronage, Institutions, and Musical Change (1927-77)." Asian Music 12, no. 1 (1980): 86-128. Accessed May 2, 2016.

- Hamied Ansari. Egypt, the Stalled Society. Albany: State University of New York Press, 1986. 183.

- Ibid. 184.

- Tarek Osman. Egypt on the Brink: From Nasser to Mubarak. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2010. 130

- Ibid.133

- Walter Armbrust. Mass Culture and Modernism in Egypt. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996.